And now for a terribly delayed post in what seems like an unending streak of terribly delayed posts in this space. Regrettably, I have succumbed to another disruption of a three part sequence project which I intended to finish long ago. The sequence will be completed... wait for it... In The Future.

Until then, it’s Me vs. SkidRowRadio in… This Time, It’s Electoral.

Some of this will feel dated. The spar I am revisiting, screencapping and hopefully concluding was instigated in early March, so in the thick of Super Tuesday when the American primaries were hotly and then lukewarmly contested. I would normally self-cringe for taking a time-sensitive topic and putting the finishing touches on it roughly a month after its time-sensitivity expires. And I am self-cringing, believe me, just not as strongly as I might need to. This is because I tamely believe the lateness has an out: cyber-normies won’t be exposed to this. People who experience time in internet years where days are weeks and months are years, will not be reading this.

Abnormal readers — who might be thought to represent the old normal, where “a month ago” does not absurdly feel like ancient history — are the prospected readers. My clash with SkidRowRadio (henceforth SRR) initially centered on decision-theoretical issues fraught with probabilities and uncertainties. Few of these issues remain unknown to us as of my writing this [2020-04-14]. But the developments and later knowledge (i.e. Bernie endorsing Biden) don’t make those disagreements any less steep or unworthy of reposting. SRR's responses to my criticisms, and other radical mishandlings of similar criticisms, remain, put amicably, instructive.

All this to say that I am cautiously optimistic that the disciplined reader is the one who won’t care how non-current or non-recent this technically current-events themed post is. If you do care and are wondering why I didn’t have it up sooner, skip to the bottom for a psychological sob story from me giving a detailed account of what holds me up these days. Otherwise head straight to content.

Also, I created a (hopefully helpful) visual that summarizes what I'm battling against here.

My OP seemed an innocent enough Poll:

I didn't recall this about the OP until I moved it here, but in it I anticipate and warn against derailing from the hard choice. Responders were told not to bring up hobbyhorses and the very themes SRR invoked and defended without flinching. Read just a fifth of my replies to him, then revisit what I advise against in the OP. Then ask me "How have you not put a bullet through your head yet?" to which I'll half-sarcastically say I dunno.

With that, we forge ahead:

SRR: “It's ironic that you present these loaded and problematic questions as requiring simple yes/no answers.”

It’s ironic that you have to answer “yes” or “no” after being asked things like “Is X strategically better than Y?” with unlimited space for reason-giving. What an empty complaint. I never even hinted that he is barred from elaborating to his heart’s content. All I do is encourage long-windedness and caveats. If these questions are so off-putting that no amount of elaboration behind a decisive Yes or No sustains intelligible discourse, just don’t answer. But he answered, despite my concerns being all but useless? Why? Because he is incapable of disengaging when a debate goes sour and when it has no prospects of a recovery. It’s tedious and I would not pull the same on him on an issue he cares about, in his neck of the woods.

Me: (Q1): You are too preoccupied with “what” questions and are deeply inattentive to “how” questions. Yes or no?

SRR: “no. The 'how' is simply to have a fair playing field. Without the electoral college and super delegates, without a bias media and rigging of primaries, a progressive candidate would have a much better chance. Obama won a big victory in 2008 by pretending to be a progressive. That he wasn't really one meant he got an easier ride to the Whitehouse.”

Me: The response is a gish-gallop, a common resort here. There is more to the ‘How’ than cultivating a fair-playing field: The unease of creeping brinkmanship, the discouragement of social chaos and riskiness, the promotion and sustainment of political legitimacy, to which I’ll return.

But one has to stand in

awe at how comfortably he recites points I’ve taken to task earlier and

arguably dismantled. Take tennis scorekeeping analogized to the EC; neither process rigs its respective contest. Acknowledging this doesn't commit you to being any less critical of the methodologies behind the tallies.

This counterpoint was ghosted, which puts pressure on me to restate it again,

which I shouldn’t need to do.

When someone is convinced that a voting system is roundly

illegitimate, they must be prepared to object to it and fully denounce its

results no matter who comes out on top.

Can anyone seriously picture SRR or Bernie’s supporters doing this had Bernie

emerged victorious? Can anyone picture it with the supporters of a

Bernie-adjacent candidate from the future? Do you see them putting as much

emphasis, or any emphasis, on the participant-independent and process-dependent

features, like the EC, the super-delegates and other

procedural impurities in an alternate timeline where irregular voters come out in droves for Bernie or someone

like him as his campaign predicted? Where the justice-seeking candidate makes

quick work of Biden or the DNC stooge and advances? This is unimaginable.

Forget full-blown dismissals of the outcome on the demerit of illegitimacy, no one even complains about the mechanics when the horse they’re backing is in the driver’s seat. So spare me.

Next up: complaints about a biased media. By media he means the old media, because New Media is seldom guilty of the apparent anti-Bernie bias the traditional media is said to be. This is so important, it sees its way into an answer to a query about the What and the How. And here too, the original link to the Hostile Media Effect from way early in the exchange was not taken into consideration during answer time. I won’t repeat myself ad nauseam. SRR and anyone who thinks he makes a strong point will have to follow the link and tell me what those findings mean to them. Even if these senseless-hostile-effect discoveries turn out to be wrong or non-generalizable, and hardly any media consumer interprets non-slanted coverage as slanted, it means a knowledgeable Biden enthusiast is suddenly in a position to extend the bias complaint to the stridently progressive influential outlets and talking-heads who are clearly biased against anything DNC. From there the Biden backer may posit that were it not for the tech-savvy broadcasters’ stranglehold over digital media, heaps of young voters wouldn’t have voted Bernie and would have realized that Biden is their guy.

Suffice it to say, this would be a sorry excuse for an explanation behind why their guy (counterfactually) lost. And doubly so in a context where the Biden supporter had been tasked with explaining why the proposed Disaffected Voter turnout for Biden was much lower than his campaign assured everyone it would be. It’s effectively saying: This group of people who normally stay home wouldn’t have stayed home, but they watched YouTube pol-gurus like Kyle Kulinski shit on Biden daily in countless videos and were therefore dissuaded from voting Biden. By staying home.

If it sounds petulantly straw-graspy when you turn the tables, it’s because it is. But this is just what the excuse for the low-Bernie-turnout rests on: Registered voters who stayed home, to avoid voting altogether, being duped by the MSM to favor Biden over Bernie. I can’t even.

Just bringing it up out of the blue is perceived as a subtle “fuck you” directed my way because I have dealt with it earlier, and here it’s a scurvy workaround to grappling with the more difficult “What vs. How” triage question I was curious about.

Next, SRR says Obama won 2008 by pretending to be a progressive. Obama the faker. Once again, it’s unrelated to the question and just twists my arm into distraction mode, because it begs a different question in ignoring the eat-shit-and-compromise nature of national politics. In 2000 Bush ran on a campaign that ended up looking pretty estranged to his eight years in office. Are we to deduce that Bush is a “fake” conservative by the same lights? Or do we acknowledge that shit happens? When it does, the visionary morphs into the functionary like a good chameleon should and must.

And just like Bush, Obama won reelection despite the visionary-functionary transformation. I assume that no one will dispute that the reelection campaign Obama ran was plenty less ambitious than his wide-eyed bid in 2008. So by this point Obama would have been ousted as a fake progressive — however the hell SRR wants to measure that, no comprehensive pro forma metrics are ever given by lockstep decriers of fakers — to the oh-so progressive electorate. Yet this 2012 turncoat Obama still won and managed to with ease. A reasonable person absorbs this and accepts that Obama's 2008 victory didn’t hinge on what SRR says it hinged on (tricking progressives). A reasonable person accepts the bland truth that a charismatic Democrat doesn’t need to pander to devoutly progressive hardliners to win elections in a country like America. A reasonable person accepts that the pundit’s fallacy is in fact fallacious. Few voters operate in ways the (old and new) media presents. Upon discovering this, the consumer of political science is thankful for the information, while the political hooligan tells himself a story about the info's irrelevance, or just blocks it out full-throttle.

Damn, that’s just my answer to his (non)answer to Q1. This is going to suck.

Me: (Q2) The political spectrum conceals aspects of political reality and strategy much more often than it sheds light on such issues, as per the reasons I supply in a previous comment. Yes or no?

SRR: “2) not necessarily. If you know how to observe what's going on. Just cos the spectrum is skewed and seeks to obscure matters, doesn't mean you can't still have a robust analysis of the problems with it.”

I was thinking of something not-so-subtly different.

What I had in mind: political thinking ought to be provisional and non-doctrinal. Call this view political provisionalism. Call the view it’s reacting to political doctrinism.

Doctrinists are everywhere. They believe that certain prepackaged ideologies are truer or wiser or better than their canonical rivals, and that doctrinal superiority can be cashed out in a fixed, content-dependent way. Provisionalists on the other hand deemphasize the role of doctrinal content and put a tremendous amount of weight on people’s professed beliefs and their revealed incentives. The truth-status of incentives has to be accounted for because what people think they’ll do (and not do) versus what they’ll actually do (and not do) is important interpersonally (so ethically) and is to a larger and larger extent ascertainable by first-rate social scientists.

Whereas the potential mismatch between what people profess to believe and disbelieve versus what they actually believe and disbelieve is harder to pin down, and is arguably undoable when the dormant belief the social scientist is trying to unlock is highly abstract (political beliefs are generally very abstract). This difficulty or impossibility speaks against the delinking of professed beliefs and informed consent in political life. The two were oft-delinked through a web of Manufacturing Consent style expositions.

So even if our consent is dimly manufactured, it wouldn't follow that the Chomskyan revealer of this loathly affair gets to be the stand-in authority on what non-manufactured consent would have looked like under ideal conditions. If a consent-giver is estranged to or bemused by his genuine belief despite a first-person advantage, a social engineer with his third-person disadvantage won't fare any better at getting to the bottom of it. So provisionalism calls for an evaluative subjectivism about political beliefs while striving for an evaluative objectivism about incentives (to optimize good>bad behavior). [Extra weight should be placed on interpersonally-entangled incentives, which you could argue comprise most incentives, given how rare it is to find someone who is so disconnected from others to the point where his true incentives and behavior impact no one but himself.]

For provisionalists, Ideology X can be better than Ideology Y after all, but this is only so in a recognizably tentative, content-independent way. Sure enough, Ideology X can never outdo its competition in the traditionally declarative way we have been accustomed to hearing the doctrinist tell.

Set aside worries about revealed incentives and bring into view worries about professed beliefs, and the mechanism for conflict resolution reduces to “Majoritarian Will > Minoritarian Will” elegance. Factualism would still have a place; a majority that tests poorly (i.e. significantly less in touch with observable reality) would not be given the world on a silver platter. It is only when a majority and a minority are misaligned on pre-factual points of contention, while being closely or evenly matched on their knowledge or ignorance of the facts, that the majority voting bloc would get its way. Here majoritarianism would settle disputes much more often than the rigid setups of today and yesterday allow for. I call this the Crude Elegance approach to conflict resolution. Crude because it overlooks the incentives bisection to get off the ground, elegant because its belief bisection is a plain numbers game; free of political Sacred Cows and nearer to neat-and-tidy.

Worth stressing is that saying no to doctrinism and its perverse monisms doesn’t mean the theorist further denies the necessity of constitutions, procedures, conventions and other rote processes, because those are methodical norms which are instrumental inputs. Such inputs are important because they are measurably adept at attending to people’s revealed incentives (minus beliefs). I realize this is an odd-sounding line in the sand to hang on, but I must fuss over it, since I don’t see doctrinists making the basic belief/incentive distinction, ever. The doctrinist holds that codified constitutional rigidity or materialist rigidity or contractarian rigidity is justified on pre-incentive grounds or pre-factual grounds, even when a considerable majority takes the constitutional law (or materialist law, or contractarian law) to be invalid or illegitimate and is left feeling civilly alienated. This is a mistake. Let constitutionalism serve as the example: Whenever you have a constitution a majority takes issue with, where this majority is also bound by the tenets of this constitution, and where no substantial or objectively verified boon to proper incentives can be linked to the presence and endurance of the constitutional order, however directly or indirectly, this is enough to ground substantive constitutional reform. Whether this reform moves things resolutely “leftward” or “rightward” or whether it’s an unadventurously moderating force, will be uninteresting to the based provisionalist, for he is more empiricist than theorist. What's needed for something uninteresting to turn interesting is for enough of the subjects to (i) understand the constitution, (ii) disagree with the constitution overall, (iii) give minimally sound reasons and withstand counterpunches from the minority defending the status quo, (iv) be disposed to see themselves shoddily incentivized by the constitution they wish to reform or overthrow more than the one they intend to codify as its replacement (or by the non-constitutional scheme they plan to implement as its replacement).

This is all to say that provisionalists won’t be alarmed by how leftward or rightward or centered policies skew at any point. In sounding the alarm on a spectrum-based notion of decline, the provisionalist would need to draw attention to actual incentives and explain how recent policy developments create more impediments than fillips. For financial incentives in particular, he would discuss how i.e. in Singapore a market-dominant approach reliably comports with the closest-to-optimal incentives compared to a mixed or planning-dominant approach, whereas in Sweden a mixture of planning and markets seems to hit the closest thing Swedes have had to an “incentive sweet spot” and consistently so.

This is not to deny that a

nontrivial number of Singaporeans would be better served by a less

market-dominated incentive scheme, or that many Swedes would be better served

by a less mixed and more market-friendly (or planning-friendly, for others)

incentive scheme. It’s just to say that — assuming

the research I’ve done intermittently for over a decade on these two countries

and their peoples hasn’t misled me empirically and left me in the dark —

the financial incentives dispositional majorities

actually respond to are well-suited to the economic norms in these two places. Dispositional minorities will lose out, in both countries, and that’s the price of

doing business regardless of the incentive scheme we try optimizing for.

According to the orthodox and heterodox political spectrums, what I've just proposed does not take the form of a coherent view at all, and is a nebulous vacillation. To which I heartily say: This is your brain on the political spectrum.

Returning to the belief bisection: If we seek the most informative returns from datasets on the economic beliefs of average people, the first places to consult and survey are those whose citizens experienced the best (or worst) of Both Worlds. So basically, Eastern and Central Europe.

Recently Pew published results from a rigorous "30 Years After The Fall Of The Iron Curtain" questionnaire. The feedback unearths patterns that provisionalists should have no qualms taking to heart, and that doctrinists can be expected to, in the best case, hem and haw over:

If a resilient enough incongruence exists between professed beliefs and actual incentives among the surveyed, the takeaway is a thorny one and is beyond the scope of this post. But in the absence of such incongruence, the provisionalist responds to these findings with "Other than Russians, and to a lesser extent Ukrainians, the post-Soviet shift to economic liberalism across Eastern and Central Europe was a serviceable shift". Doctrinists are left questing for a sweeping account of why one or another vision is right and why accommodating the convictions of mere mortals within each country is wrong. For market purists or principled anti-socialists, the majoritarian outliers (Russians, Ukrainians) are simply empirically mistaken to deviate from the trend. For market abolitionists or principled anti-capitalists, the rest of Europe is simply empirically mistaken. How about that?Returning to the belief bisection: If we seek the most informative returns from datasets on the economic beliefs of average people, the first places to consult and survey are those whose citizens experienced the best (or worst) of Both Worlds. So basically, Eastern and Central Europe.

Recently Pew published results from a rigorous "30 Years After The Fall Of The Iron Curtain" questionnaire. The feedback unearths patterns that provisionalists should have no qualms taking to heart, and that doctrinists can be expected to, in the best case, hem and haw over:

It's not even the intellectual hubris that repels me, but the willingness to universalize a soft science like economics; trying their darnedest to shoehorn its truths or insights into a tightly blueprinted box. An ex ante box, nowhere near spacious enough to house the vagaries and complexities of modern life; from Black Swan events to less extreme curveballs which no theory can anticipate and incorporate into its blueprints pre-hindsight.

Now I need to say something about how we might formulate “basic good incentives” versus “basic bad incentives” desiderata in a non-doctrinal way. This will be a brief sketch, as these replies break SRR’s brevity standards too much as it is. So: A basic good incentive encompasses those behaviors which in the long haul produce outcomes congenial to one or another welfarist-leaning perspective (and perhaps robustly welfarist perspective). Because they’re not wedded to the triumph of one preset ideology or set of ideologies over another preset ideology or set of ideologies, provisionalists may further modify welfarism, as with desert-adjusted variants. Doctrinists may doubt that there is nothing political going on here, and would in a very narrow sense be justified in thinking this. A welfarism that explicitly guides our thinking about politically salient good vs. bad habits is a welfarism that no longer enjoys a 100% apolitical standing. Nevertheless, what sets it apart from the pack is its lack of doctrinaire structure and thus its unconcern with the defeat of one familiar societal vision and the ascendancy of another.

But sure, identifying and fostering good>bad incentives in service of broadly welfarist ends does rule out certain political sacred cows more strongly than it rules out others. It is one thing to notice that broad welfarism has a tendency to be amiable to secularism over non-secularism, to representative democracy over participative democracy, or to positive liberty over negative liberty. But to assume that provisionalists are blind to seeing that any such trend is potentially reversible, and that those three goods are theoretically abandonable, would be a misreading. Everything is open to reexamination, and not in the disingenuous "open minded" lip-service way, but rather with the understanding that the identity and self-esteem of the reexaminer aren't implicated. The uncaptured reexaminer feels no urge to launch into fight-or-flight defensiveness due to a once air-tight precious principle losing steam. The closed nature of political doctrinism leaves its admirers psychologically deficient in the face of such duties.

In the past I figured the

pragmatism/idealism divide to be a good fit for what I'm now calling provisionalism and doctrinism. I will distance myself from pragmatism because too many people who think of themselves as pragmatists aren’t psychologically attuned to what I personally want pragmatism

to be. For many, pragmatism is just another tool for actualizing a doctrine or a loose set of doctrines. That is; the pragmatist will merely tolerate the discarding of this or that set of ideals, and only for the time being. Such a pragmatist may still cling to the hope that the people might some day undergo changes so seismic (in values, attitudes, customs, habits, incentives) that an ideological unity or non-plurality will be implementable with no losers. Nothing about this contradicts pragmatism, though it appears fantastical in the eyes of provisionalists like myself.

I've had this on the backburner for over a year and never managed to finish the post it was supposed to be used in, so here it is: (click to enlarge)

That is what I wanted for pragmatism. From now on I'll be calling it provisionalism.

Here's a Quora poster perpetuating the semantic hellscape popular commentators have nourished by refusing to toss out the spectrum. In assuming that its definitional premises are uncontested, pundits encourage this gibberish by omission:

While his main point is accurate (rampant misuses of fascism), the path getting him there is paved with an arbitrary and analytically meaningless taxonomy. But I'm sure he has a story about why it's the right one to use, which explains why he also misuses fascism towards the end.

Spend just five minutes a day for a couple of weeks reading political posts on Quora and you'll come to the dispiriting realization that its users are drowning in this homespun-spectrum crap. And there's no talking them out of it.

Recall my Bush/Obama remarks from Q1. What I omitted to mention is that Bush is called a “fake conservative” by propertarian minarchists and strict constitutionalists (originalists, textualists). These people understand Obama to be ultra-progressive. As we saw in Q1, Obama is called a “fake progressive” by those who would insist that the soaring militarism of the Bush administration is, far from unexpected, the natural consequence of a conservative winning the 2000 election. According to them, Bush is at home within the conservative diapason and anyone denying this is out to lunch.

The provisionalist notes that neither camp has persuaded the other that their self-styled recognition of fakeness (Dubya’s non-conservatism or Obama’s non-progressivism) gets at the truth. SRR seems untroubled by this, whereas I’m incensed by it; it's not going away and the prospects for non-paranoid, cross-ideological mutual understandings grow ever dimmer.

While his main point is accurate (rampant misuses of fascism), the path getting him there is paved with an arbitrary and analytically meaningless taxonomy. But I'm sure he has a story about why it's the right one to use, which explains why he also misuses fascism towards the end.

Spend just five minutes a day for a couple of weeks reading political posts on Quora and you'll come to the dispiriting realization that its users are drowning in this homespun-spectrum crap. And there's no talking them out of it.

Recall my Bush/Obama remarks from Q1. What I omitted to mention is that Bush is called a “fake conservative” by propertarian minarchists and strict constitutionalists (originalists, textualists). These people understand Obama to be ultra-progressive. As we saw in Q1, Obama is called a “fake progressive” by those who would insist that the soaring militarism of the Bush administration is, far from unexpected, the natural consequence of a conservative winning the 2000 election. According to them, Bush is at home within the conservative diapason and anyone denying this is out to lunch.

The provisionalist notes that neither camp has persuaded the other that their self-styled recognition of fakeness (Dubya’s non-conservatism or Obama’s non-progressivism) gets at the truth. SRR seems untroubled by this, whereas I’m incensed by it; it's not going away and the prospects for non-paranoid, cross-ideological mutual understandings grow ever dimmer.

I think most of this gets propped up by the madness of groupshift. The preconditions for groupshift: uncontrollable pride, mulishness, bellicosity, intellectual immaturity, and the social-trust model of belief formation as the cherry on top. Definitional dead-ends follow; quadrupling-down on a term's true interpretation; reassert your definition enough times in enough debates, essays or speeches, and the doubters who refused to run with your definitions for decades will roll-over and agree, any day now. This is still around in 2020. What else could it do but foment balkanized epistemology the way we've seen? It is not a sustainable program for conflict-resolution, and you need some measure of

conflict resolution to govern effectively.

One interesting application of provisionalism is found in Scott

Alexander’s nutshell hypothesis from 2013 which holds that “rightism

is what happens when you’re optimizing for surviving an unsafe environment,

leftism is what happens when you’re optimized for thriving in a safe

environment.” He calls it the

thrive-survive theory of the political spectrum. So how safe are we? Evidently, some places are safer than others. It's only trivial-sounding because the carryover to political ideology is ignored: Some places are safer than others, therefore some political communities ought be more progressive than others. It's tempting to follow with: Ah but how safe is The World? Here I would encourage the art of sticking to what you know or have the capacity to know/learn. For factualism's sake. If you think yourself capable of scouting the overall safety/unsafety state of The World, even statistically, you overestimate your brainpower (or any other fallible individual's brain).

If thrive-survive fails explanatorily, I’d like to see a

refutation. Mind you it will need to be a comparative refutation; refuters ought

to show why doctrinaire theories carry more explanatory punch, and how they fare across the epochs and geographies. Sounds like a doomed project

to me. Thrive-survive is very much imperfect, but because it focuses on conditionality and circumstances over doctrine and vision, it offers more explanatory insight next to the

orthodox and heterodox theories which rely on first principles.

From the same post, Scott writes: “Libertarians say that leftism supports government intervention on economic but not social issues, and rightism supports government intervention on social but not economic issues. Unfortunately, this isn’t really true. Leftists support government intervention in society in the form of gun control, hate speech laws, funding for the arts, and sex ed in schools. In fact, leftists are sometimes even accused of being in favor of “social engineering”. Meanwhile, conservatives lead things like the home schooling and school choice movements, which seem to be about less government regulation of society.”

Whatever its first-order oversights, thrive-survive suffers less misanalysis at the metacognitive stage. Until exponents of doctrinism show otherwise, thrive-survive ought to count as another strike against invariantly principled theories of politics. None of this takes away from the previously mentioned strikes (resistance to evaluative subjectivity for professed beliefs, weak attentiveness or inattentiveness to evaluative objectivity for actual incentives). It adds to them: Find yourself living in a predictably enduringly safe environment and you'll be rounding-off your policies sharply leftward, and in a correspondingly rightward direction when you’re under threat, and further still depending on the higher level of threat.

And that's what's wrong with the political spectrum.

Me: (Q3) My analogy to score-keeping rules and premises in professional tennis is well-placed and shows that it's illegitimate to cry "rigged" prior to changing the rules. True in tennis. True with elections. Yes or no?

SRR: “3) no. Tennis and elections are very different. The equivalent analogy would be that the umpire prefers one player and awards more points per ball won to that player. And of course you need to cry rigged BEFORE a system is changed. How else do you expect the lack of fairness with an unfair system to be addressed? You could even legislate to prevent bias in media, (via laws against monopolies and representation etc) which is a peripheral issue but intrinsically linked to the riggedness of the entire system.”

Saw this and went “Ah damn I blanked on having asked a separate question about the tennis analogy. Guess I should remove what I wrote as part of my answer to Q1 where I bring up him ignoring the tennis analogy”. But after reading the reply in full, there’s no need to erase anything. At no point does he explain how the entrenched norms are illegitimate (i.e. unconstitutional). I find them intensely disagreeable — they stack decks against democratic campaigns competing in down-ballot races — but this doesn’t prove them illegitimate. Political theorists often take legitimacy and justice to be non-overlapping political magisteria. Were they cut from the same cloth, avid reformists would have to believe that so much of what transpires within the policy-world is illegitimate atop unjust.

Much of it is, if you ask me, nakedly unjust. But if justice and legitimacy were to merge in political theory, a rogue state would be as illegitimate as a state that does one or more of the following; holds open elections, oversees peaceful transfers of power, stands for a free press, due process, freedom of conscience, freedom of assembly, freedom of occupation, commits no human rights abuses… but implements thousands of unfair policies as a norm anyway. Both states would be denounced as illegitimate, even though one violates basic and nonbasic liberties with abandon, whereas the other violates only the nonbasic ones. For more on how legitimacy differs from other political goods, see the SEP entry on it.

But if democrats were to be more proactive in protesting the current gerrymandered system on backward-looking as opposed to forward-looking grounds, which currently existing law or set of laws would they need to appeal to? This question is open to anyone. I’m genuinely at a loss, and it’s why I believe the Electoral College system in America is better challenged on forward-looking grounds. This presents one of those "it's a tougher sell, but it's also the stronger argument" problems forcing civic agents to choose between integrity and efficacy.

Me: “(4) Does Bernie Sanders show any signs of having a legislative strategy? If so, where do I read up on it?”

SRR: “4) his job is to win the presidential nomination. If he wins, its his role to try to implement his program. If it is blocked by a resistant establishment, that's another battle that will need to be fought. His program would have been deemed popular with the country, if the elites in Congress, the senate etc block it, they will be further exposed as enemies of the people. Got to start somewhere. Do you think it would help Sanders electoral chances for him to constantly talk about how awkward it might be to implement his whole program? That awkwardness is not on him. It is on those who would block it. They'd love to see him essentially throw the towel in before he even gets chance to try, by admitting that the system he seeks to change will likely resist that change”

He could’ve just said “No he doesn’t” or “Maybe, but I’m not going to waste time trying to look this up, you’re tiring me out”. Instead we get “Once blocked by a resistant establishment, that's another battle that will need to be fought”. The pesky truth about these future fights is: you never win them cleanly and always rely on grand bargains across party lines. If the hypothetically emergent Bernie administration was so inclined — concocting bargain after bargain with congressional republicans — there would’ve been a similar enough backlash against him that we saw manifest with Obama. That’s the larger point, and firebrand progressives need to stop denying and coping when presented with arguments for its repeatability.

Bernie would have had three options: (i) be an inefficacious leader who refuses to bargain, refuses to indulge executive overreach, and gets nowhere as a result, (ii) milk the executive overreach option to the point of absurdity so as to avoid the backlash-prone transactional path, as well as the inefficaciousness, (iii) come around to the transactional approach and implement, at best, somewhere between one third and one half of his agenda.

(iii) would be his best bet, given the importance of legitimacy — which would be compromised should he overplay his hand through executive powerplay. But we have no idea what to predict, because he never made it a point to be upfront about these tough choices, hence my reasonable question.

When SRR says "enemies of the people" it's as if he's thumbing his nose at the efforts I've made and the lengths I've gone to so far in this exchange to show why politically observant, active or passive Americans do not comprise anything close to an electorate that can be understood under a rubric of populist-resistance-to-elite-rule:

"Democratic senator Joe Manchin represents a state whose median income is $45,000 a year. He is among the most conservative Democrats on Capitol Hill, and said in 2019 that he would not vote for Bernie Sanders in a race against Donald Trump. Manchin’s House colleague, Ro Khana, represents a constituency whose median income is $141,000. Khana is among the most left-wing members of Nancy Pelosi’s caucus and co-chaired Bernie Sanders’s campaign. This is difficult to explain if one posits a tight correspondence between an area’s class composition and its appetite for social democracy. But it’s much less mysterious if one presumes a correlation between high levels of education and support for progressive politics: 60% of the adults in Khana’s House district are college graduates, while just 20%of those in Manchin’s West Virginia boast bachelor’s degrees ."

SRR might as

well be sticking his keyboard-tongue out taunt-like and saying: You’re wrong, your data to the contrary is wrong; America is not splintered

along its usual constituencies, power structures and special interest gangs. The People’s

interests are united, the preeminent division is between them and the scurvy elites. Far from “injecting life” into the Democratic Party, this romantic fondness for anachronistic models of coalitional organization are on their way to incurring its death knell. The “inject life” posture draws from revolutionary electoral strategy, which I like to call Anticipatory Marxist porn. The 2018 midterms' down-ballot results should have been the final nail, but here we are.

No concessive attitudes have floated about in

Classical Marxist and other Marxist quarters, up until and including the post-primaried current year. Their cherished class-realignment, class-identity strategy has bombed more than once. In lieu of a reevaluation and some soul-searching, we are treated to more of the same; more finger-pointing at the wicked establishment and its proxies; more stunted excuse-making unable to cope with the fact that most primary voters support the Democratic Party. What a bunch of babies.

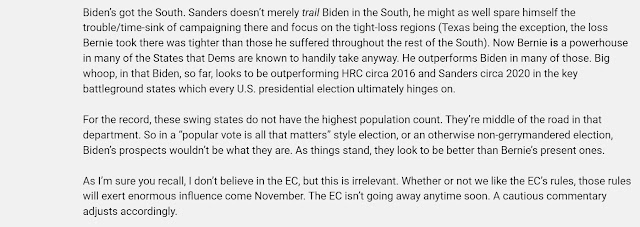

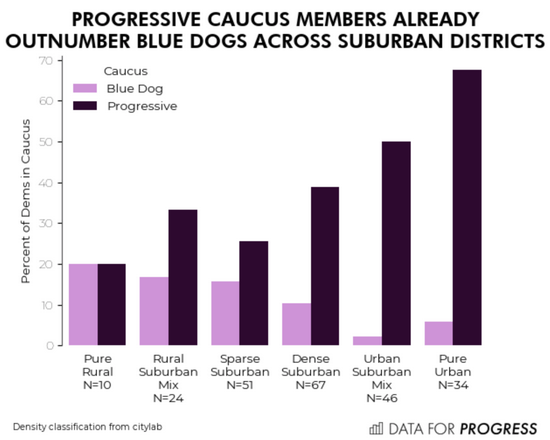

How much more handwringing and electoral misfiring can we expect to see from class-realignment theorists until they start to face facts? Facts say the suburbs are the electoral golden goose. Rural districts are the electoral wild goose. The unfortunate lingering influence of Industrial-era Marxism has progressives chasing gaggles of wild geese. Apparently this is something SRR would like to see progressives keep doing until the end of time. No, it's a thoroughly disproven electoral strategy and its failure needs to sink in.

Failure = that rustic, non-college credentialed, often low-skilled, manual-labor-intensive voter so often sought after by the anti-corporatist, anti-Blue-Dog Justice Democrats... the so-called abandoned voter? That's the voter regularly bearing the littlest fruit in manifold down-ballot races despite being solicited and coddled. Devoting time and energy to courting such voters incurs the piled-on opportunity costs of neglecting the now more observantly receptive suburban voters.

And why in the first place would a theory urge electorally-minded radicals to defuse the promise of well-credentialed suburbanites for the less decorated rustics? Because a remnant of

Marxist fabulism spins the suburban group into an implicitly suspect voting bloc; they make up the post-industrial adaptation of the petty

bourgeoisie. Suburbanites — being overrepresented in careers and roles which boost the ownership

positions that must be overthrown or gradually repealed via tactful reforms —

have

for decades been treated dubiously under such rationale. Of the two

non-ownership groups, they are the enablers. And the select few who secured their titles by way of an upward mobility

climb? They are class traitors. The uneducated or minimally educated blue-collar voting bloc is, then, treated as the anti-enablement counterforce and thus an implicit true ally.

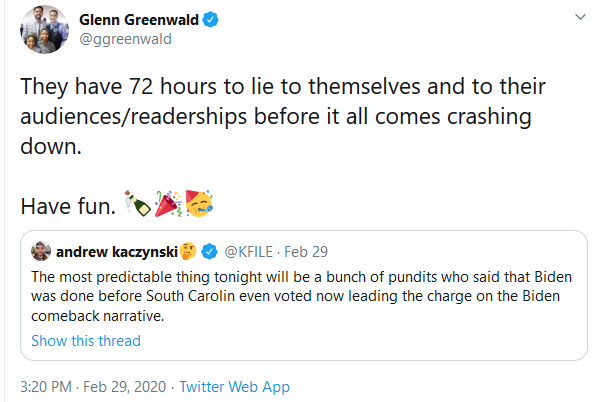

Just in case anyone thought otherwise, the above doctrinist is also unwilling or unable to see just how much egg he plastered to his own face through tweets like this. It's like the more knee-deep you plunge into election season, the more bluff-esque or poker-esque political discourse gets. But it doesn't have to be this way. People like Greenwald should make you want to hurl, even if you agree with them on every object-level issue. Their impetuous conduct should bother you more than the concrete policy disagreements of a conventionally recognized political foe who never gives in to such epistemic misconduct, and who exerts valiant effort into the art of disagreeing better.

I have wasted and might have to continue wasting time and nerves, none of which I would’ve done had the walnut-brained Bernie crowd been able to accept a few brute facts about promising and unpromising voting districts. But they are impervious to it, continuing to toil under the influence of class-centric captured thinkers — who are themselves brainwashed by older generations of noisemakers — into an insular view that claims knowledge in: fellow member of the working class = latent ideological ally.

Me: (5) Does Bernie Sanders show any signs of having a theory of change? If so, where do I read up on it?

SRR: “5/ see 4”

Me: See this.

(No, a legislative strategy is not a different way of saying “theory of change”. But thanks for not engaging, lets me move to the next question and not pull my hair out for even longer)

Me: “(Q6) All of my unanswered questions in the “Haves vs. Have Nots” response a few comments back: They are decent questions and they show that “Haves vs. Have Nots” is an antiquated way to think about both micro and macro economic policy. Yes or no?”

SRR: “6/ no. Which is easily demonstrated by the changes in policy which have reduced rights and empowerment of the working class, and increased benefits and privileges of the owners class. This is not some flippant throwaway remark, it is an indicator of a widely accepted analysis of economic imbalance. If you seriously don't think there is a disparity with how society treats the wealthy and the poor, then I really don't know what I'm supposed to say to you, maybe I should just link-fu you, as you have me, and tell you to go read some Marx or Varoufakis or Chomsky.”

Off to the races again with the gish-gallop, skipping past the crisp objections which were laid out painstakingly in the screenshot. Pointed questions were posed, like how many Haves in the world, roughly? How many Have Nots? Where to situate the tens of millions of white-collar workers and others who are compensated more handsomely than the exploitative mom-and-pop store owner, as well as the medium-sized business owner once we consult the recent past? In place of an answer or an attempt at one, he blathers about the policy hits labor sustained in a few countries starting in the 70s/80s and onward. No one who matters is lost on this history. It doesn’t lend support to the shallow and propagandistic picture that categorized laborers “Have Not” whereas the categorized capitalist “Has” all because he owns a business, now or then. Income rose five-fold in Japan from 1958 to 1987. This period did not bear witness to political revolts. Whatever can be said of the advantages of owning a business in Japan in 1958, the absolute advantages of earning money in 1987 and beyond is the superior boon when the objective truly is escaping privation and precarity.

By most measures, the ‘Have

Nots’ of today's First and Second World enjoy a level of economic security and living standards that scores

of dead-and-buried Haves couldn’t attain historically. For details, consult Gwern's post which does a masterful job reminding us how easy it is to take these slow-burningly piled-up improvements for granted, or hell, to even let them go unnoticed over a lifetime.

This is where measures

of people’s absolute gains must be understood as absolutely

superior to measures of positional setbacks. Earn between $52K

and $55K annually and you are in the Global 1%. This doesn’t answer

the egalitarian-esque worry that humans are naturally status-seeking and

comparative. Instructing them to subdue such sensibilities is asking too much, the thought goes, such that relative non-absolute setbacks should be controlled for as assiduously as, if not more than, absolute improvements. I say more about this in an old post. We don't need to travel down that road here as the more competitive, one-upmanship oriented people (oft-envious

“Status Seeking” people) and the just-trying-to-get-by “Have

Not” people, represent non-overlapping distributive dilemmas. The comparative-grievance group isn't so much a policy problem as it is a psychological puzzle with a few missing pieces.

Concerned about the Have Nots as SRR is? Stark global poverty is the category to pounce on. When you discuss it, don't leave out how over the last 25 years, modes of relief from billionaire philanthropy have decisively outperformed modes of relief by government aid. This doesn’t mean governments cannot do better, it means elected officials are on a provably steady course of being outdone by private donors. This embarrassment poses a non-negligible risk for ideologies prizing governmental ameliorative techniques over even the finest billionaire benefactors on principle alone.

Imagine going through life thinking that one cluster is true and the other is false. Imagine being unable to accept that subsets of both can be true, and consequently having your attention diverted from the hard empirical task. The task aiming to establish which claim holds up with what degree of frequency and under what types of conditions. Welcome to doctrinism!

“maybe I should just link-fu you, as you have me, and tell you to go read some Marx or Varoufakis or Chomsky.” Imagine namedropping Marx to a jaded Eastern European and telling him to cram on the finer points of Class Conflict theories — from ~150 years ago at that — during a defense of Haves and Have Nots as valid sloganeering. The temerity of this, when everyone slated to read your comments qualifies for Haves despite laboring for coin. [Edit: I am actually open to the possibility that I'm guilty of having fallen into a habit of overselling the informational and dialectic edge Mistake Theory has over Conflict Theory, whose role may be large, perhaps nearly as large, as that of Mistake's. Even then, what's inexcusable is to nod along to theorists and forecasters who took this much educative stock in Conflict Theories, leaving minuscule (if any) space for Mistake Theories, thereby walling their audiences off from noticing the civic damage done to cloistered groups (i.e. pitting worst elements against each other). Looked at socially, there is no denying that these mental models reward varieties of Type 1 thinking, from splitting to clickbait to unwarranted indignation to well-poisoning to personal-is-political intuitions, etc.]

Here’s an anti-capitalist whose writing inspired Scott Alexander to semi-popularize the Conflict vs. Mistake meta-theoretical debate within the rationalist community. Though a radical at the object-level, the OP agrees that getting policy questions right is amazingly difficult and that Conflict theory should not dominate the deliberative process. When it does, it creates a pattern of undue trust in members of the in-group. This in tandem with making you suspicious of the out-group’s motives and of some — or most, or all, depending on how conflict-captured you are — of the objective evidence the out-group’s best members happen to come upon first. Stuff like this is why conflict-theorists think in ways that exacerbate error proneness and increase the likelihood of pushing through unpopular policy.

The hyperlinked OP is mindful of this and is therefore not a supporter of the bullheaded, take-no-prisoners approach to dialogue, where goodwill is only ever a simulacrum. His object-level concerns (the eventual abolition of capitalism) do not dictate his meta-political concerns to him. How many anti-capitalists take a page out of this book? Nowhere-near-enough for revolutionary attitudes to prove innocuous, much less beneficent.

I am fine with being fu-linked, by the way. When I raise concerns and am told that it’s already been addressed “insert here” I know to do one of the following (a) check out the link, read/listen to it and argue against its claims if I find them disagreeable and comprehensible, (b) ignore the link out of laziness and/or apathy, but have the decency to keep my mouth shut around the person who went to the trouble to vet the link for me before bringing it to my attention. What I wouldn't do is continue arguing in a way that suggests I did my political homework when it's obvious to all that I didn’t, (c) read/listen to the source material and notice that I'm not quite sure how to respond to it, tell the person who recommended it that something about it seems off, but I don’t really know how to articulate what exactly, then bow out by giving the interlocutor props for pointing me to something new. It’s rare to be exposed to a refreshingly novel argument, and even though the takeaway seems off in an ineffable way, the person who directed you to it did you a favor. Unearthing newer ways of thinking is needed within politics and beyond. Practical Eccentricity is sorely needed.

So I welcome any link to a talk or a piece from the three chaps SRR mentioned, but the talks/pieces can’t just contain generalities; they need to engage with the exact criticisms I or others have made of Haves vs. Have Nots framings, and explain how I as a laborer pass for a ‘Have Not’ despite earning decent enough wages for 15+ years and never worrying about money and affordability or any other ordained causes of my eventual destitution. Further, explain how I in particular am mistaken in not centering my political ideology on the economic recognition of being a ‘Have Not’. Even if I believed myself to be a ‘Have Not’ I would not center my political priorities on this fact, due to there being at least a hundred other detached issues of grave importance weighing on my conscience. Bar none, every time I pose this challenge, I get an empty declaration that those other areas I’m fretting over (i.e. S-Risks) are less important than my aiding in the bringing about of the commons’ victory. The word-string self-evidently less important never makes an appearance, but this is the crux of it; a pure axiom. You don’t arrive at Class Essentialism; you declare it.

Class Essentialism is still around because a sophisticated intellectual tradition breathes life and aesthetic respectability into it, with greater intensity when the overthrowable status quo takes a hefty hit at the hands of a badly-shaped recession or a pandemic.

Consider what it means to dismiss the core claims of the non-astrological theologian with the same levels of confidence as you dismiss the core claims of the non-theological astrologist. Rationalists do this on the reg, despite knowing about the exalted antiquity of the theologian’s trade as compared to the astrologist’s. Still, the relatively more impressive and challenging story behind the theology trade and its contributions to the development of spiritual or intellectual public life and institutions doesn’t imbue the rationalist with reasons for taking any of theology’s more declarative claims more seriously than we do those of a particularly declarative astrology. If the vibrant history of theology does nothing to justify lending it this credibility, something similar can be said about the influential history of Marxian class analysis. Had Marx written all he wrote but in 2020, adjusted for technological and social updates, and if no one else had produced any thesis remotely similar to that prior to him, his insights would not be blowing people’s minds. It feels eye-opening because we know about its existence pre-analysis; we first have a vague sense of it as a body of works which enjoys longstanding factional canon. Canon and continuity have an aesthetic about them, and aesthetics have a way of keeping ideological factions from sundering. The aesthetic of distrusting the experts; the aesthetic of populist contrarianism, is its biggest (and arguably only) persuasive asset.

Next to universal suffrage and dark money, a mark of political power is the aesthetic of the faction flex. Non-factional people are politically tamer people. I can be mightily engaged while factionless, in which case I’ll yield about as much political power as the disengaged do; slim to none. So people want a faction, and those who are revolutionarily disposed want a stronger-than-average faction, because the task ahead for them is more monumental. This, combined with the force of contrarian aesthetics, explains why generations of thinkers continue to tinker with Marxism so as to improve it, instead of just ignoring it (i.e. due to its predictive duds). It's that simple.

Anyway, how about we change the wording; laborer is what is meant by ‘Have Not’ and non-laboring owner or investor or inheritor is what is meant by ‘Have’. While an improvement, this wouldn’t justify the dichotomous aesthetic of the analysis, considering the volume of laborers with 401(k) plans or stock portfolios, and given the frequency with which once non-laboring economic agents file for bankruptcy and become wage-earners. Maybe this is too quick, but I can’t get more precise until the laborer/owner dichotomy-monger or the laborer/manager/owner trichotomy-monger tells me how many people belong to the unjustly dominant economic group or groups. When the final tally is no longer obscured, we can look at economic mobility data (and different types of it) to try and get some idea about the relevant correlations. i.e. is more macroeconomic interventionism into the economy strongly, weakly or inversely correlated with greater levels of economic upward mobility? Are there actual trends here, or is it too scattered for a systems-centered takeaway? (I suspect too scattered)

These are challenging questions that, to my recollection, none of the thinkers SRR relies on have addressed. If they have, SRR or a sympathizer can point to the relevant passage or interview. Until then, douchy namedropping followed by “read them” won’t do.

I am positive that none of them, including their followers, have fresh ideas to contribute. Since they try to cast wide listenership or readership nets, they are fine with speaking in loose generalities about the perilous risks poor people face because they are poor, or the debts to society the rich skirt because they are rich. Indeed, the first thing to bring up here is the unfairness of bail in the penal system. Oh look, the link takes you to milquetoast as fuck NPR. They’re hosting someone addressing a hardship that disproportionately impacts the poor. Why wouldn’t they? The discrete threats facing the poor form discrete issues and policy challenges. An anti-piecemeal, systems-first top-down approach has been counterproductive too many times in the past to count as a rock-solid solution.

What do you suppose are the odds of Chomsky or Varoufakis — or anyone else SRR thinks

I’d do well to read — having visited or plugged Robin Steinberg’s Bail Project site? If they haven’t promoted it, as

Richard Wolff by all accounts has not done (mentioned here because he’s listed as an influence on

Varoufakis), it might have to do with them being preoccupied working the latest

angle for the Big Picture showdown; wanting so badly to see the system fall that

they willingly look past such lowly initiatives. The rationale: If bite-size reforms go nowhere, the financially strained and

wrongfully detained may be driven to the brink of furor, and past it; enough to erupt against

the system, something the radical direly wants.

If one grants that the laborer/owner divide is as primary for grasping today’s political struggle as it arguably used to be two centuries ago, this still wouldn’t tell us why labor/capital is the most relevant intra-economic divide. I would love to know where, if anywhere, Marx, Chomsky or Varoufakis address the prominence of other grouped economic battles and explain what makes them less relevant than the acute laborer/non-laborer conflict. Think about the jostling for supremacy and advantage between the economic agents in finance vs. industry, exporters vs. importers, creditors vs. debtors, productivists and their critics, fiscal expansionists vs. fiscal hawks, or even boomers screwing millennials. Most of these divisions arise from conflicts internal to labor itself. People don't need private property protections to exploit anyone. All that's needed is to gain leverage over an individual looking to make ends meet. Leverage comes in many forms, sometimes the product of some people having cultivated advantageous habits and others having given in to disadvantageous ones. It’s easy to see how this would continue to happen in a private-propertyless world, and how readily it would give rise to worker-on-worker exploitation.

But oftentimes the leverage phenomenon is just the product of dumb luck (or at least the weaker form of luck that discounts habit-formation as ripe for genuine luck). Both of these go some way in explaining why the still exploited worker has put himself in a compromised position; noting the role of imprudence over systemic oppression.

Worker-on-worker exploitation can be generational. I noted the boomers, as majorities of them stood for policies which caused or exacerbated many of the financial hardships younger people have had to endure. The exact number of individual boomers who are guilty/complicit is unknown, but it’s a large enough percent to be worth the mention. I'm sure we've all read or glanced at dozens of pieces written by an under-40-something op-ed columnist bemoaning the fact that their grandparents handily paid for college with summer jobs, reared up to four brats in a single income household, fully paid off the homes they started to own in their twenties by the time of their early thirties, never stressed over eviction or bills again, managed to obtain and keep medical care without health insurance, and never ran into the kind of medical bankruptcies the under-forty crowd is notorious for dealing with. But all these people labored under capitalism where the government steered clear of (large segments of) the economy.

Either the ownership class is absolutely necessary to prevent the boomers from enjoying what they enjoyed (disproven), or the elimination of it is absolutely necessary for subsequent generations to enjoy what the boomers had (unlikely). This is why class essentialism is a deliberative dead end; rather than punishing the analyst when he does his best to drown out the remaining intra-labor tussles borne of public choice problems, it rewards having one particular tug-of-war reign conceptually supreme. The inter-generational, intra-laborer disputes show that for worker solidarity to sustainably work, you have to shut off your brain and sweep aside generational and other salient differences within the glorious workforce.

The point is not to lend support to a one-dimensional “Boomers vs. Non-Boomers” mindset, as so many supporters of Gen Y and Gen Z are under the thumb of. It’s to show that a unidimensional frame rallies around cherry picking and selection bias where a multidimensional one is free of it. The generational essentialist blocks out that which the class essentialist hones in on, and vice versa. To get around this, one must widen the frame; broadening core conflicts to look something like Four Networks Theory.

Me: (Q7) People are making a grave mistake when they say things like “I’m done trying to change hearts and minds” because that type of mindset is a precursor to political thuggery and brinkmanship. Yes or no?

SRR: “7) no. What I meant by that is I don't care if you agree with me or not. Because I don't hold any delusions that I'll be able to convince you. I'm barely even confident we are able to agree on our disagreements. You're quite insufferable to debate with BTW. You write essays and demand essays in return, which if I did reply with this sort of length each time, would only exponentially increase the length of your already excessive responses, and this would turn into an insanely protracted debate, which I'm sure you still wouldn't be satisfied with. So, brevity has its uses sometimes. Don't assume that brevity = lack of insight. You insist on extracurricular reading/listening, which you arrogantly assume would make a difference to an opinion you assume is based on frippery, yet you yourself litter your responses with logical fallacies, assumption, condescension, non sequiturs and other problematic aspects, all the while behaving as if you are the arbiter of logical discourse. Your distain for my approach is not justified. As for thuggery, discourse is the key to changing minds, of course. All I'm saying is I don't care to spend weeks on end being told I'm doing it wrong, & being insulted and condescended to. You've decided Im just a flake, so why would you want to solicit detailed responses beyond my statements of how I see things anyway? The changing of minds happens in much less involved exchanges than you seek. Trump got on podiums and shouted basic, populist aims and convinced enough to back him. Where and how do you see your favoured approach being applied in wider society? To win elections you must inspire people at a visceral level. Sanders message of a fairer economy resonates with younger generations. What place on the podium for this sort of discourse? You'd be a shit candidate.”

What logical fallacies? Name them.

“I

don't care to spend weeks on end being told I'm doing it wrong” Then leave

and don't come back. I should have pleaded for this right after the second

round of my replies went nowhere. “so why

would you want to solicit detailed responses beyond my statements of how I see

things anyway?” Because you are in my

space and I only let unaggressive arguers have the final word when an important

debate unfolds on my turf. You are not being unaggressive, so I am drawn to reply

and pose challenge after challenge for your blinkered class politics, in the

hope of drilling some humility into you (perhaps you think I also suffer from a

deficit in humility, and I'll defend against that if need be).

I asked question 7 because earlier SRR said that he’s done trying to change hearts and minds of others. In the answer here, it’s about his inability to change my mind. So that’s off point. But if I remember wrongly and it was about my mind all along, I don’t understand why he continued to engage me even though he was blind enough to think that I was bringing nothing to the table and was insufferable. “You insist on extracurricular reading/listening” No, you can do whatever you want with your time. All I’m owed is having the person who insists on continuing to show up on my page with flippant replies to be able to summarize the points against him. If I thought any of these (data rich) arguments I linked to had been commonly made, I would not push you or anyone else to read/watch them. “You've decided Im just a flake, so why would you want to solicit detailed responses beyond my statements of how I see things anyway?” Because you wouldn’t go away. Had I been this critical of you on a post you made, away from my channel, putting you on the defensive in your own space, I would be in the wrong. That’s not what happened though. Your persistence + Your unwillingness to check out a single source that refutes an assumption you operate on = me being nasty to you.

I would be a shit candidate, absolutely. I neither deny the effectiveness of demagoguery nor wish to take advantage of it. Excoriating the influence of billionaires, as if they’re an ideological monolith, resonates with a segment of well-tempered voters (atop a much larger segment of ill-tempered ones), but that doesn’t stop it from being demagogic and nonsensical. By all means, argue for a fairer economy, but the moment those arguments elide or distort something I know to be true, I’ll make a scene of it.

Me: (Q8) The anti-capitalist doesn’t persuade anti-socialists of anything by abolishing their preferred system from the top-down. He persuades them by first accepting that workers of all stripes face the same problem they’ve always faced; collective action problems, trying to coordinate workers from bottom-up, trying to establish commonly held standards of fairness from workers after finally getting them to coordinate from the bottom-up, having them pool their resources and smarts together, ultimately showing through action and organic organization that they don’t need to rely on private employers to operate their own businesses. The extent to which he fails at this reveals the extent to which workers actually do depend on a private employer. Yes or no?

SRR: “8/ the anti capitalist doesn't need to persuade the anti socialist, he just needs to persuade enough of the electorate that his way of doing things is better. An anti socialist is inherently a bit of a cunt and will not be convinced by any means. But the wider populous is not anti socialist, they dont identify either way, they just want to live in a fairer, kinder society. Its up to the anti capitalist to explain how why we ended up with such imbalance and cruelty. Collective action problems were caused and are maintained by capitalists. So yes you'll have to change things from the top down, as well as enabling workers to organise from the bottom up. I'm not sure why you think these two efforts are mutually exclusive? "to operate their own businesses" what percentage of workers would ever strive to or be able to operate their own business? Who are you pitching to here? Most would be employees, not employers.”

You don’t inherently

need to be a bit of a cunt to resist an ideology whose conventional applications scale the private

sector down to zero. Not down to 20%, not 10%, but rock-bottom zero. You need only accept the strengths and weakenesses of modern governments; the types of services they are decent at delivering versus the roles they’ve consistently been indecent at. I would assign more reading

material in the way of data-sets, but

won’t because that’s obnoxious when overdone apparently, but as an established

rule: the public sector is better suited to delivering services and essentials (with a nod

to non-rivalrous goods) whereas the surplus-taking private sector is better suited to delivering products

and luxuries with a nod to rivalrous goods. Since

modern economies are incomprehensibly jumbo-sized, expect for there to be more

unessential goods and services in production than the essentials. And since there's no reason

to think that this will change such that agrarianism (or something) gets

re-throned, the private sector should in a country like America outsize

the public sector by a ~70%/30% margin. This means sticking to some

version of capitalism, and it would spell “some version of capitalism” even if

the total demand for non-rival services rose to match the total demand for consumer goods. That's going by one nation's econometrics, so a kindred rule of thumb may not hold elsewhere, though I see no plausibility behind a 180 departure away from 70/30.

Some patterns are global: Individual consumers use up sheerly private goods. Food is probably the most consistent example of this. Even in villages, a meal is typically eaten by one person. Bob's use excludes Jim's ability to consume the same meal. People may share food with their

close-ones or with destitute strangers (through food banks), but only one person

can eat any given serving of a meal. Because private goods are bought and consumed, unplanned supply/demand laws describe the efficiency dynamic of private goods as well as can be expected, so the collision of private demand curves and production supply curves predicts the appropriate pricings and quantities. What do market

abolitionists say to this?

Public

goods are at the opposite end of the continuum. Knockdown examples include public

health services and the internet. The characteristic that distinguishes a pure public

good from a pure private good is that one person’s use does not impair the ability

of others to simultaneously make use of it. Bob and Jim are equally

protected by a publicly subsidized fire department. For that reason,

traditional supply/demand stories are slated to misidentify how much fire

department funding to produce and how

much each citizen should pay to prevent against potential future harms. Since no profit-seeking firefighter firm could charge citizens individually, no

market mechanism exists to identify how much each citizen is willing to pay.

What do moronic exponents of voluntarism or anti-statism say to this?

To condense: Mixed economies, with mighty pendulum swings and all, aren’t going anywhere because the nature of goods/services calls for mixing.

All this to say: Contrary to SRR’s well-poisoning, the skeptic of unmixed socialism isn’t necessarily dismissing it on dickish grounds. SRR should be epistemically interested in this type of anti-socialist, not in the knee-jerk parochialists who were indoctrinated into hating socialism.

But you would need to be a bit of a cunt to favor scaling tax-transfer programs down to zero, as there is no complicated logistical issue at the bottom of that. Opposition to social spending is almost always moralized, and is not to be conflated with the cost/benefit questions and other issues in public choice theory setting limits on how large or multitudinous the government should be.

“Collective action problems were caused and are maintained by capitalists”

In other words he never bothered to learn what a collective action problem is: (a) Joint goods: Effortful contributions to collective action can create private benefits for those that act, in addition to public benefits for those who sit on their asses and contribute nothing. (b) Preference heterogeneity: Some folks value collective action highly and others value it minimally (i.e. the civically minded vs. monomaniacal self-seekers). The costs/benefits of a given contribution to collective action will vary across individuals. (c) Increasing returns: Action in the past can decrease the cost and increase the benefit of action in the future, while also changing how people value and prioritize collective action.

Bounded rationality and irrationality is at the heart of collective action problems, not a cabal of greedy profiteers. People don't naturally excel at thinking algorithmically about decisional problems. Witness terms like satisficer replacing terms like optimizer in the relevant literature. We generally suck at this stuff. Studying decision theory can help, but very few people are taught decision theory and most go through life with schismatic decision-non-procedures guiding them. Enter human failure to cooperate under even ideally controlled conditions, like in social experiments where the subject is insulated from the externalities of the terrible awful no-good system. Even there, we fail to cooperate like clockwork. Decades of replicated experiments (i.e. ultimatum games) have lent support to this, as I like to call it, cognitive pessimism.

I swear next he’ll blame capitalism for the procession of cognitive biases widespread in the population.

“But the wider populous is not anti socialist, they dont identify either way”

Where did he get that impression? Anti-capitalists seem drawn to it because they equivocate between capitalism the role and capitalism the belief. But SRR says “identify” which suggests he had belief in mind.

I will track down and source to the following from Pew if need be: Over three quarters of Americans were found to be tolerant of private investors, so of activities producing gains through investment; everything from common shares and preferred shares, to regular interest and compound interest, to plain old savings accounts. Over two thirds were tolerant of employer/employee contracts against which the LTV stands. Ending exploitation entails outlawing these avenues for moneymaking. Americans increasingly believe in setting limits on how much investors and owners can enrich themselves through the stock portfolio or the wage-contract, but this is not enough for SRR’s point to land, as Classical Socialism seeks to prohibit — not just put a ceiling on — all of it. Ceiling-talk is considered to be bougie halfway measures.

(But disclaimer: Advocates of Market Socialism plausibly don’t need to go that far, at least with respects to interest-derived gains, and I will have to re-acquaint myself with the subtleties of their take on markets to see if the synthesis pans out. For our purposes here, their take is an afterthought at best. SRR is objecting to the market dimension of capitalism, putting him at odds with the market socialist all the same)

“I'm not sure why you think these two efforts are mutually exclusive?”

The underwhelming performances (to put it mildly) and paper-trails of Marxist states with a vanguard party structure. Time after time, it is the cadres, not the masses, who end up calling the economic shots. And because Marxist doctrine tells them it’s foolish to disentangle economic and political issues, they are subsumed under a single organizational domain. This gives way to anocracy at best and oligarchy at worst. No, I’m not convinced it’s an inevitability, but it's enough to make you think of parables about the madness of trying-the-same-thing-over-and-over-and-over-expecting-a-jackpot-each-time.

But why do Marxists continue to rinse and repeat?

Here’s Marxist economist James O’Connor: “In Marxist theory, the "liberal democratic state" is still another capitalist weapon in the class struggle. This is so because the democratic form of the state conceals undemocratic contents. Democracy in the parliamentary shell hides its absence in the state bureaucratic kernel; parliamentary freedom is regarded as the political counterpart of the freedom in the marketplace, and the hierarchical bureaucracy as the counterpart of the capitalist division of labor in the factory. (O'Connor, 1984, p. 188.)”

Here’s William Domhoff on O’Connor’s passage:

“There are some Marxists who would say that this is really the Marxist-Leninist view of representative democracy, not of Marxists in general. Be that as it may, the point for now is that this analysis is often accepted as "the" Marxist view by new Marxists, and is identified as such by O'Connor in the passage quoted above. I think it is a crucial point to consider because the idea that liberal freedoms are really a thin veil for the repression of the working class, when combined with the idea that the market is inherently exploitative, generates a contempt for liberal values and democracy that leads to crucial misunderstandings of the United States. It says that representative democracy is all a sham. I think this may be one of the root problems of Marxist politics in the United States, a problem that makes it difficult for Marxists to join into coalitions with liberals. For those Marxists who see representative democracy as a sham, the solution is "direct democracy," meaning small face-to-face groups in which the people themselves, not elected representatives, make decisions. This is in fact the meaning of the term "soviet." But historical experience shows that such groups came to be controlled by the members of the Communist Party within them. Problems also developed within direct democracy groups, often called "participatory democracy groups," in the New Left and women's movements in the 1960s. Although they tried to foster open participation among equals, they developed informal power structures led by charismatic or unbending members. There came to be a "tyranny of structurelessness" that shaped the group's decisions, often to the growing frustration of the more powerless members (Ellis, 1998, Chapter 6; Freeman, 1972). Based on this experience, it seems that selection of leaders through elections is necessary to avoid worse problems. Rather than downplaying the elected legislature, as some Marxists do, the Four Networks theory suggests that the creation of legislatures was a key factor in breaking down the unity of the monarchical state and thereby limiting its potential autonomy. Put another way, representative democracy and legislatures are one of the few counterpoints to the great potential power of an autocratic state. They should not be dismissed as inevitable mystifications of class rule, even if empirical investigations show that legislatures in capitalist societies are often dominated by capitalists, as is generally the case in the United States. The idea that Marxists and liberals should agree on is to extend the openness of legislatures in ways discussed in the Social Change section of this Web site.”

Me: (Q9) It is wise to accept the transactional nature

of politics as political practice. Yes or

no?”

SRR: “9) huh?”

Upper-echelon political bargaining, as in, the undercurrent of compromise. See Brian Tomasik’s “Gains From Trade Through Compromise” for more (it’s not a must-read, I’m just really impressed with it and like to circulate it any chance I get.)

Since civic agents have bumped heads over the basics and will continue to differ no matter where you look, it’s unlikely that principle-distorting compromise will evaporate from political life along a timeline accessible to us. If a doctrine claiming to be political doesn’t enshrine Openness To Compromise into its theoretical fold, it will suffer for it operationally. Unlike non-political theories that aren’t constrained (or as constrained) by practical considerations, a political theory that’s bad in practice (because uncompromising) is ipso facto bad in theory. People tempted by a “fuck compromise” Molotov-mindset need to forget politics and focus on futurism or something. Unless they want civil wars.

Me: (Q10) Are establishment Dem vs. GOP appointed Cabinets equally bad?

SRR: “10/ depends on the policies they pass. Red or blue makes no difference if they're doing the same things.”

Depends is a skeleton-answer at best. Putting some meat on the answer for him: And since they seldom “do the same things” in the real world, they are not equally bad in actuality. They can pass nearly identical legislation in certain areas, like prohibitive drug laws, but they’re never equally bad across the board. An unwillingness to zoom out because both parties ran afoul of your wedge issue, is petulance pure and simple.