Have philosophers developed an adequate taxonomy for interrogating the most mature divides and zigzags on life and existence as bearers of disvalue or value? If you believe that they have, tell me what you think that is. For instance, which descriptor best summarizes your outlook on life? Which descriptor have your mortal enemies adopted? Are these terms prodded by assessments of lives as they are in actuality, or are they licensed to go a step further by assessing matters as they might be, however plausibly or implausibly?

What’s a complete outlook on life anyway? Do speakers owe their audiences a theory of meaning, or are they justified in remaining silent about the arguably hazardous possibility of meaninglessness despite their eagerness to advance a lucid theory of value/disvalue? Would subdividing 'meaning' along cosmic vs. terrestrial lanes make any real difference?

Should armchair-derived outlooks have their own labels, or are they better kept overshadowed by the formal and orderly labels philosophical evaluators have come to depend on?

Should armchair-derived outlooks have their own labels, or are they better kept overshadowed by the formal and orderly labels philosophical evaluators have come to depend on?

If you think this terminology can be covered by anti-natalism and natalism, or by anti-mortalism and pro-mortalism, or by the more conventional and general standoffs between pessimism and optimism, I humbly ask that you rethink those picks as you read through this.

If your main philosophical interests are remotely like mine, you might think that a more precise lingo is covered by the deluge of isms we have attained from population theory (totalism, averagism, geometrism, etc). Think again. I’ll press for the avoidance of population theories’ descriptors as well, because they serve different purposes and classificatory ends. Retracing my steps, I see that this literature is something I raved about as recently as 1.5 years ago. I now suspect it of being too damn technical for its own conceptual good, believe it or not.

Granted, most of those technicalities fall closer to what I’m gunning for here than what any ism in procreative ethics aims at. But population theory in its current guise misses the mark too, and will continue along this path for as long as it solicits modal and temporal inputs for ironing out what are supposed to be non-modal and non-temporal (or semi-temporal) gridlocks.

What I have in store here can be thought of as Value Theory vis-à-vis Population Theory but without the trifling modal complications and with only marginal temporal influences – influences way slenderer than what celebrated population theoreticians like Hilary Greaves lob at us.

The evaluative impasses emerging from some people valuing life and others disvaluing it are bound to persist even after the wildcard of modality is stricken from the equation. Following years of agnostic silence, I have mustered the commonsensical intellectual courage to brush off all things modality – like the inexplicably respectable modal realism – with a swift “To hell with this”. After participating in this poll and seeing so many others vote the way I did, I stopped caring about the arguments in any detail and just splurged on commonsense full-throttle. Reassuring stuff. I guess my having needed hundreds of people to shrug off modality right along with me before feeling comfortable enough to take to the blog with my shrug, makes for a philosophical-bystander-effect. How embarrassing.

Consider also what it means to put absolutism on trial in moral philosophy and to hang it. It’s so easy, but I can’t think of any philosopher who actually carries it over to value theory for a pre-moral scrutiny and hanging. Value pluralists? Please. Not if they’re forced to be fully consistent on the matter, something one never sees happen. It may have happened, but I’ve not seen it. I should have seen it, as I’ve read my share of pluralist vs. monist contestations over the soundness of a unitary supervalue from which all other values derive, with pluralists denying the thesis and monists affirming it.

The “seminal” works of foundational pluralists like Judith Jarvis Thomson, W.D. Ross, Bernard Williams, Christine Swanton, David Wiggins and Charles Taylor all overlook the unmentioned threat of abandoning absolutism. It’s not that there are unaddressed threats across the board for those who wish to resist the supervalue. There is just one; life the blessing as a domain of intrinsic value absolutization. None of these thinkers’ main works grapple with the idea of pluralism as a rightful barricade to tolerating the intolerable; a threat to the threat absolutism originally posed. Yet this is what a fitly recognizable pluralism has to be; a force at odds with life presented as a lexically-protected intrinsic good.

Omitting to address this, the mentioned pluralists subtly welcome an existential absolutism that cannot be made to fit in with the otherwise foundational pluralist program. Maybe none of them have mused far enough ahead to perceive it as a contradiction or an internal difficulty. But they’re giants, so it is more than likely that at least some of them have gotten around to it, and have concluded, perhaps unwittingly, that the alternative is best not given a voice as it calls for too unconventional a paradigm shift in value theory. I have little doubt that the seminal works of countless other pluralists with whom I am unfamiliar leave them in the same boat. They can be counted on to dodge the challenge too, unwittingly or not, in the name of convention and aversion to what (from the outside looking in) feels like conceptual morbidity.

I am aware that this is an assumption. Assumptions are fine when they are justified. This is an entirely justified one. For it to be unjustified, intuitions propping up a lexically-protected blessed life would be hotly contested in contemporary philosophy, given the breadth of pluralistic influence on the terrain. But it’s not contested. It doesn’t even have a name or a category through which it can be called out, for Pete’s sake. The dearth of contest shows that even the most influential pluralists don’t care to sound off on the matter.

Now, I am not implying that these thinkers are inattentive apart from this wrinkle. Pluralists are loudly pluralistic and pensively meticulous in their treatments of intrinsic value, such as in carving out standards for the good life. Not so much when it comes to registering the mounting intrinsic disvalue from one generation to the next and reckoning with all the bad lives, and certainly not in the role they let (or don’t let) commensurability play (or not play) between intrinsic value and intrinsic disvalue. Supervalue insisters can intelligibly defend their refusal to let commensurability get a foot in the door when the commensurability threatens supervalue. Those who deny the viability of supervalue, cannot.

Pluralists on intrinsic value: It takes a multiplicity of intrinsic goods to live the good life. Securing valuables x/y/z gets you there, unlike tales of the supervalue which belong in the dustbin. I tell you we are so studious and attentive in precisifying what makes a life go well, a growing number of us now believe that the trajectory of a life matters too! An uphill life is superior to a downhill one, even when the two lives are otherwise identical in their obtainment of goods and avoidance of bads! :-)

Pluralists on disvalue, all but whispering: Hmm I guess most people are nowhere close to satisfying The Good Life’s criteria as set forth by us. Seems like this is one of those things that has serious implications, all of which are existentially incorrect, so let’s discuss something else forever. :-)

Compare: The Philosophy Of History. "There are no laws of history, there are only contingencies!" (says the contextualist to the historicist)

Compare: The Philosophy Of Sociology. "There are no sociological laws, only contingencies!" (says the contextualist to the... vanishingly few sociologists who would actually argue with the quote)

Crucially, a contextualist can be more mortified and irate at the present state of things than a given absolutist can be, and may strive to convey this with a sturdier negative ruling relative to that of the absolutist's. But he will know to leave it at that and invoke no laws or meta-philosophical themes to his talks. Moreover, he will know to never speak of life as if he hasn't left it at that, no matter how casual the banter he partakes in becomes. Whether in the midst of a fireside chat with a BFF who never gives pushback to anything he mouths, or a circle-jerk with strangers who happen to be his philosophical replicas, the pessimistic contextualist will stay true to this condition. In all conversational contexts, he will feel the regulative pang of the anti-law view. It will cast a humbling, posture-averse shadow over every thought he has; in relaxed private settings, combative public settings, or dialectic settings.

So a mature theory of existence is one that vindicates evaluative pluralism, closes itself off to being absolutized, shuts down hypotheses of mood-based paths for enhancing truth-perception skills, and renders its tenets deeply context-sensitive. This sees contextualists tethering the goodness and badness of how individual lives actually go with the goodness and badness of what it meant for those lives to have come into existence and what it would mean for them to prematurely end.

For reasons spelled out in Part 1, this destabilization need not involve the ethics of procreation whatsoever. The badness or goodness of coming into existence doesn’t (necessarily) imply anything by way of wrongness or rightness for the moral agent who knowingly and volitionally caused someone to exist. The moral value realm is its own beast. It may require an overhaul of the culpability trisection standardization I introduced in Part 1. [Since that post went up, I have discovered a growing body of literature devoted to probing the conditions necessary for moral responsibility to have bite. It is a more complex and multifaceted problem than I had surmised. I will say (much) more about this in Part 3. Yes, there will be a Part 3.]

The contenders:

Existential Adventurism: Acknowledges that life is unspeakably bad for some number of individuals and asks So what?

Affirms life.

Existential Rejectionism: Acknowledges that not all lives are equally bad, that some lives are much better than others by any measure, and asks So what?

Affirms life.

Existential Rejectionism: Acknowledges that not all lives are equally bad, that some lives are much better than others by any measure, and asks So what?

Denounces all lives.

Existential Preventionism: Takes seriously the separateness of lives and with it the dissimilarities in life outcomes and qualities. Adjusts evaluative standards accordingly. Resists affirmations as well as denunciations of sentient existence as such.

Prioritizes the prevention of unacceptably bad lives over the promotion of good lives, including the best ones, and even the ideally perfect ones.

***

These are not neologisms. I’ve merely transferred existing terms from the policy-world into my world. As taxonomic twists, I think these three have what it takes to bring clarity where the old taxonomy fell short; to succeed as workarounds to the hyper-abstract contaminants of modality and temporality.

Also, I bring optical fun and assistance:

(Just a warm up optic showing how my newer terms relate to the established ones, or how I personally picture them relating to each other. Missing are the global/local prefixes to the familiar terms, because we’re taking it one step at a time…)

Adventurism = a type of existential absolutism.

Rejectionism = a type of pessimistic absolutism.

So what’s left?

Preventionism if you ask me:

Bubbled overlap represents my own sense of cross-ideological tolerance levels between global and local anti-natalisms, and more importantly, between the two of them and existential preventionism. There is much harmony between global anti-natalism and existential rejectionism, naturally. Other than that, rejectionism enjoys zero harmony with any view.

But what’s left for pluralists who want no part of preventionism either? Hard to say:

I should rephrase that: What’s left for faux pluralists who think of themselves as legit pluralists but who want no part of preventionism either? Well, that we know: Some type of non-adventuristic evaluation of things that ignores its own wink-and-nudge and valorizes life all the same.

Preventionism = pluralism done right.

Non-adventurism and non-preventionism = wannabe pluralism.

How can I defend the insinuation that pluralism, contextualism and preventionism are natural allies and that everything else is a misguided absolutism or value theory done wrong?

I begin with the rejectionist outlook and its overreaches.

Existential Rejectionism

Thesis: Living is intrinsic disvalue on arrival. Anything we might think of as worthwhile or good (i.e. pleasure, eudemonia, desire-fulfillment, achieved goals) is relief-based. This holds regardless of the degree to which someone is better off than someone else. The only time it may not hold is when someone is perfectly off, something no welfare subject has ever known or can ever know. However, even if they could know it in some fantastical future, nothing truly valuable would flow from it. Procuring such a state would only subvert the bad.

With this flag planted, every living person falls short of being a bearer of isolated positive value and no one escapes being a bearer of isolated disvalue.

Rejectionists accept that new people can on balance improve the world, but this gets at siphoning standard instrumental value from the improvers. It is a boring point, as drab as the one about instrumental disvalue at the hands of those who worsen the world. Whether a new person heals or spoils the world, they are bound to be bearers of isolated intrinsic disvalue to the extent that their own needs are imperfectly satiated in the best case, and grossly deprived in the worst.

As a practical belief, existential rejectionism can be explicitly cognized, tacitly intuited, or anything in between. Whichever form the belief takes, it’s hard to see how certain of its bullets are to go unbitten when we reach the question of pro-mortalism, and Global Pro-Mortalism at that.

Remember, this is not an exploration of the moral ramifications of anything, including global pro-mortalism, so any reductio counterpoint banking on the absurdity of mercifully murdering contentful people for their own good, is entirely off limits. Whatever pro-mortalism’s faults turn out to be, they will be unrelated to the crazed-mercy-killing objection and others like it.

Equally fascinating is the non-moral, prudential avowal of global anti-natalism and dismissal of the local versions (i.e. childfree versions) in all cases.

A dismissal can also be anticipated when it comes to the unacceptably placatory anti-natalism that a preventionist is poised to forward. For instance, I submit that an ideal anti-natalism will be weaker than the global kind and stronger than the sanitized childfree kind. But for that point to land in the best possible way, I would be veering towards ethics again, however minimally, so more on that in the next installment.

The pressing question for now: Is there a pipeline between [1] rejectionism, [2] global pro-mortalism and [3] global anti-natalism?

Here’s the late Jiwoon Hwang on pro-mortalism, in response to Benatar’s efforts to dislodge the notion that any view of death could be read as a natural sequel to DB's formulation of global anti-natalism:

Spot on work by Jiwoon here. Regardless of how someone’s life is actually going, the isolated boon embedded in that person promptly ceasing to exist is a natural offshoot of the immodest procreative asymmetry DB has advanced. Coming into existence (prudentially bad) and out of it (prudentially good) must be evaluated inseparably once DB and other global anti-natalists call the shots via temporal inflexibility. Should an aberrant theory of welfare or interests be resorted to as a way of negating the in=bad/out=good connectivity, the same theory would suffice in undermining the in=bad bisection on the very basis it sets out to undermine the out=good bisection.

This goes to show that procreative asymmetries are only ever morally commanding, and should not be “axiologized” or “temporalized”. Here’s an example of a modest asymmetry by Hermann Vetter that passes the smell test and doesn’t imply anything like the in-therefore-out offshoot:

We have a simple deontic imbalance at work: Duty violations abound when people procreate, and are spotlessly unviolated or fulfilled when they abstain from procreating.

For a non-deontic asymmetry to take hold, it would need to institute temporally-infused elements, which forces the institutors to make unsubstantiated assumptions about the solubility or insolubility of longstanding problems in the philosophy of time (among other things). I don’t think we need to be doing any of this. I believe in conserving as many of our parsimonious heuristics as possible wherever it’s plausible to.

So to my knowledge, no one has successfully de-linked the pipeline.

So what, the rejectionist will balk. What’s the problem with global pro-mortalism anyway? Why shouldn’t the abrupt cessation of any given person's life be viewed as an isolated improvement in a strict prudential sense?

For a non-deontic asymmetry to take hold, it would need to institute temporally-infused elements, which forces the institutors to make unsubstantiated assumptions about the solubility or insolubility of longstanding problems in the philosophy of time (among other things). I don’t think we need to be doing any of this. I believe in conserving as many of our parsimonious heuristics as possible wherever it’s plausible to.

So to my knowledge, no one has successfully de-linked the pipeline.

So what, the rejectionist will balk. What’s the problem with global pro-mortalism anyway? Why shouldn’t the abrupt cessation of any given person's life be viewed as an isolated improvement in a strict prudential sense?

Braced for it?

The curious case of Joanne Cameron.

I’ll quote a paragraph from this piece, but try to understand that a full reading is obligatory for the anti-mortalist opening to set in, and sink in. Joanne is just the sort of unrecognizably lucky person whose story cannot be done justice with a few excerpts or summations. So I implore everybody to read (or listen to, the audio feature will be to your left) the full exhibit. Only by inhaling all of it will you come to appreciate why Joanne is, if not perfectly off from cradle to grave, certainly optimally immune to all of life’s noteworthy edges, and arguably imperfections, enough to overhaul the catchall bleak claims rejectionists spout as a norm. The argumentative norm for why existing just plain sucks.

“In addition to her unusual emotional composition, Cameron is entirely insensitive to physical pain. As a child, she fell and hurt her arm while roller-skating, but had no idea she’d broken it until her mother noticed that it was hanging strangely. Giving birth was no worse. “When I was having Jeremy, it was the height of everyone doing natural childbirths,” she said. “My friends would come up to me and say, ‘Don’t listen—it’s murder. If you’re in pain, take everything they give you.’ I went in thinking, As soon as it gets painful, I’ll ask for the drugs. But it was over before I knew it.” Remarkably, Cameron didn’t realize that she was any different from other people until she was sixty-five. “Lots of people have high pain thresholds,” she said. “I didn’t think people were silly for crying. I could tell people were upset or hurt and stuff. I went through life and I just thought, I haven’t hurt myself as much as they have.””

I don’t expect an ideological sea change from hardliners as a result of this person’s life. Not overnight anyway, which means pushback in the near term. A creative pushback, let’s be clear. It would need to depart from the argumentative norm, as Joanne’s ordeal is provably insusceptible to all that. Call the foregoing of this norm the Otherwise Neglected Reasons for why life always sucks or why dour narratives and declarations about existential laws are all-encompassing. Imaginative pro-mortalists and rejectionists, have at it.

But when you’re done, tell me what would an eternal supply of nothing but Joanne Camerons spell in your mind? Simple doom?

Simple doom! A stimulative regularity would be catapulted into one spanning for an eternity. But what if a never ending stockpile of Joanne Camerons actually hits the existential sweet spot? So confident am I in this, I would press the “Joanne Cameron On Loop Forever” button in an instant. That’s an act, and again, I don’t mean to assess the deontic status of acts in this post, but still it’s clear what I’m getting at, apart from it involving a button that someone literally has to press. I’m getting at: The future that our actual world is headed towards is looking to be considerably more undesirable than the one with Joanne Cameron on loop, even though the one we are marching onward to guarantees the cessation of all life somewhere down the line, whereas the looped one guarantees the opposite.

Rejectionists, global pro-mortalists and global anti-natalists must ask themselves: Which future am I more perturbed by?

How you answer a question like this speaks volumes about where you stand on the below finality-prone world as compared to the life-for-eternity one. The latter contains heaps of welfare subjects who, let’s suppose, aren’t as impeccably well off as Joanne is, but who are still better off than those who actually motivate our calls to suffering-attentiveness ordinarily:

I chose the Sufficiency principle as my example of the “finality vanquisher” in this chart, but note that being a stalwart sufficientarian is not a precondition for being a preventionist. If it were, preventionism would be up for absolutization through the sufficiency principle. A theory dedicating itself to a unitary principle is a theory that cuts its ties with pluralism.

While preventionism casts out aggregative formulas in circumstances like these (i.e. threshold-averse formulas under circumstances identical or similar to those in the chart), it takes no stance – and turns it into an anti-stance – on the remaining available formulas within the lexical-inferiority-adjusted option set. For a general defense of those formulas, and what grounds them, see Simon Knutsson’s “Many-valued logic and sequence arguments in value theory” superb paper. The point is, preventionism is a large tent that houses a multiplicity of aggregation styles congenial to inferiority-thresholds.

Preventionism is further shaped by its denial that there is a philosophical obligation to arrive at a deep truth or knowledge beyond this. There is, for example, no obligation to rank-order all or any threshold-sensitive formulas from best to worst. Even if acquiring such knowledge turns out to be a task that humans or post-humans are cut out for, there is no obligation to come to know it now. Even speculating about it in excess is discouraged.

Compare: While it is epistemically better to grasp/solve infinite regress, a cognizer constrained by a mammilian brain is under no epistemic obligation to grasp/solve infinite regress. Know implies can. Don't waste your mind on impossible problems. By going after less ambitious problems, we put our minds to better use. This is true even for the rare genius who exists right now and who (hypothetically) does have what it takes to solve a problem like infinite regress, but who has no reason at all to believe that he is endowed with such cognitive gifts, and who downplays this, but still strikes epistemic gold in the end anyway.

But I digress.

A halfway merciful thinker should have no qualms judging the life-for-eternity world to be the more desirable one, despite it not having been wiped clean of all burdens. But if the likes of Joanne Cameron, or anyone slightly or moderately worse off than her, qualify as victims of existence too, the finality-marked world cannot be seen as just a little superior to the eternity one. It’s not even moderately or greatly superior to it. Those ways of putting it are understatements to say the least. The finality-marked world would have to be incomprehensibly, universally, infinitely and absolutely superior to the alternative. But this is madness.

A rejectionist or global pro-mortalist or global anti-natalist who immerses himself in the chart, grasps the stakes, and bites the intended bullet, has lost the plot utterly. The stipulations being what they are, an unchanging fixation on eternity suffices as the paramount example of suffering-focused views starting out with intuitive evaluations from the heart (during youth), adjoining the various unintuitive influences of the cerebrum (incrementally as youth wanes) before eliminating any trace of the work the heart did to get the ball rolling, and doing it under the banner of pessimistic wisdom or compassion.

We mustn't entertain an ideology or evaluative program that demands that we elbow-out the role of the heart fully. It’s one thing to say that the heart and the intuitive take are to be refined, it’s another to throw them overboard on the basis of their uselessness or obstructiveness in helping us solve a non-mathematical math problem.

(Victim of the Australian wildfires)

If selecting the Joanne Cameron On Loop future accomplishes nothing other than sparing this lone animal from enduring its grisly end, it will have been worth it. Even if you insist on splitting hairs on the good/neutral/bad essence of Cameron’s life and her having come into existence, you should still be willing to have her brought into existence in perpetuity, when doing so means a sorrowful episode like this one is undone.

And so, whether or not the extinction of all life eventuates is not a central worry for preventionists. The central question looks at the context behind and composition of harms and burdens. It is my hope that one day these baselines are embraced by all pessimists, but don’t hold your breath on that. If offered the opportunity to have this go viral, I would decline it. The arguments could use more polishing, but even if they were perfected, I would prefer to see anyone other than myself ride the hypothetical preventionist wave, so that I could use up whatever time I have to focus on tougher philosophical problems.

Besides, I don't sense a receptiveness in the air, not from rejectionists or adventurists, and I fear myself too impatient at this stage to play nicely for any extended period of time.

Briefly in 2017, I fell into the habit of bringing up theoretical Omelas but with a twist; I deducted the enslaved child, thinking it would make debates more riveting and get me into pluralist-friendly territory with the hardliners. This was back when I viewed global anti-natalists as something like philosophical allies with whom I could grouse about the occasional credal-based misfiring and little else, despite having had reservations about global pro-mortalism back then too.

A soft dissonance crept in and strengthened following each invocation of a victimless Omelas. I simultaneously felt that Omelas-minus-the-slave was worth a discussion, and that positing such a place was too fanciful to count for anything. I thought both these things, keenly aware that these discussions are understood as being theoretically-skewed for a reason. Feasibility should count for something, even though it strictly speaking doesn’t. How strange. I wound up feeling slimy for continually pushing the victimless adjustment and for having started to. At the same time, I felt ever more irritated at seeing my questions get ducked, or worse, answered with a defiant No, Omelas minus the slave is still hell, it just has one less victim, which is good, but nowhere near good enough.

Joanne Cameron’s life puts all those fair/unfair-move anxieties I dealt with to rest. Learning about pain asymbolia achieved this on a smaller scale, but nowhere near convincingly enough to warrant the emphasis I’m putting on Joanne. If global pro-mortalists are correct in believing that all lives are bad and not worth resuming, then Joanne’s must be nominally bad and only barely not worth resuming. It is peculiar and a bit off-putting; engaging in hair-splitting over what constitutes crossing the border between minimally bad living and non-bad or good living, and having so much ride on the answer's precision. Splitting hairs; the sort of move that gets us closer to understanding the wisdom vs. unwisdom behind a person’s continued living. It leaves a sour taste in my mouth.

Joanne is not the only person fortunate enough to enjoy a lifelong immunization to some type of ailment, but she happens to be the only publicized case whose immunities are this well-rounded and potent. I certainly don’t recall anyone else who has been covered by the press and whose immunity strength matches her level. It’s a life characterized by both physical and psychological painlessness. I had a vague sense that such conditions existed, but was never exposed to a concrete example where multiple harm-exonerations saw themselves all rolled up into a single body and physiology. These exonerations go beyond seeing the welfare subject basking in genetic predispositions to happiness.

But I've said enough about Joanne as an insulated welfare subject for now, and not enough about the uninsulated underside, like those living with genetic predispositions for major depressive disorder.

Which gets me to…

Existential Adventurism

When someone is under the impression that they are checkmating an opposing view by noting that its implications are life denying, they may be a devotee of adventurism. The attitude crops up no matter how unrelated it is to the item being debated. For instance, talking about bullying with the understanding that interventions can be a force for good, but that traditional methods seem to only make matters worse for many targeted kids, and that guardians or caretakers need better tools for weeding out effective methods from the counterproductive ones, only to be told by a newcomer late into the debate that we are all mistaken from scratch as the pro-intervention aim is a life denying signal. I will assume that every reader has observed or engaged these types at least once, and that the (gasp!) life denial example is not estranged to anyone.

Existential adventurists conceive of life as a journey above all else, and believe that it should be a ceaseless journey. This can take the form of a practical belief, a personal desire, a lofty ideal, or something to strive towards technologically and communally; a tangible plan. Henceforth, I will present it as a practical or philosophical belief only, without a program or plan or organization; just the belief and the reputed wisdom behind it.

As a practical belief, it can be explicitly cognized or tacitly intuited or anything in between. Unlike the rank-and-file, adventurists don’t suffer from optimistic cognitive biases, and their didactic ammo is not diminished for it. Adventurism offers no empty promises; no bold predictions about a pleasanter tomorrow. Adherents feel zero unease about not knowing what’s in store. They will be the first to grant that progress is wobbly, that the future is dauntingly unpredictable, that it may turn out to be agonizing for a vastly greater share of the total population than is customarily predicted, and that each individual’s agony may be much more intensely felt compared to present levels. Indeed, we should not close ourselves off to the possibility that the harshest sufferer today may be oblivious to what deep suffering really is. Despite these sober recognitions, adventurists would maintain that a lifeless future is always inferior to any life-bearing one.

This means adventurism about existence is evaluatively threshold-averse, and not only when the bad is measured in pure welfarist terms. The future may also be morally worse than anything we’ve read about from the past or observed in the present, containing unfathomably more immoral acts, sordid intentions and general ill-will on the part of individual agents. The spikes in viciousness or callousness would be immaterial, just as threshold-averseness for being badly or terribly off in a welfarist sense is believed to be immaterial. Lifelessness would still be judged as inferior.

The future may also look unimpressive from a desert-adjusted welfarist lens, with gaps between welfare received and welfare deserved burgeoning exponentially, but never becoming wide enough for the adventurist to even consider disavowing his prescription that life be an everlasting venture.

It doesn’t end there. The future may also be epistemically worse than the present, containing unfathomably more false beliefs, unjustified beliefs, uncalled for certitudes, unduly strong convictions, and in general more thoughtless and starkly ignorant people than what we see in the past and present. Escalations in dishonesty, ignorance and intellectual arrogance would, again, prove unpersuasive, as with the previous three categories of worseness.

Add to this a rise in any other (dis)value-bearer you might be drawn to; from metaphysics to aesthetics. Nothing would change. The adventurist’s threshold-aversion and negation would extend to them all. Living is the point, the only point.

We might think of Nietzsche as the utmost example of an existential adventurist, having produced a dense body of texts for us to gush over or recoil at. Amor fati owes its relatively popular station to him above any other philosopher. Tasked with identifying the summit of adventurism, look no further than amor fati.

So before you ask “Does anyone actually qualify for this bizarre adventurism?” recall that Nietzsche has long had his legion of adorers and propagators. Flecks of this legion are comprised of literary buffs who appreciate the man on stylistic grounds, but the bulk of it plunges deeper than that.

And while people may at times misinterpret his points and lessons – Nietzschean scholars put in ample work to rescue each other from misunderstanding him – the correct interpreters are not those who for nearly a century have futilely tried to recast him as something he never was; panoramic parodist, continental genius, amoral spreader of moral banality.

He was a literary giant, but this doesn’t transform the ‘immoralist’ ideas he championed into cutesy amoral musings. He had actual views, plain as the day, he understood them to be consequential and wasn’t afraid to spread them. They scream unyielding adventurism about existence, as described above or in uncontested wiki entries. Hardly faultless, for a self-appointed masked prophet.

Before I add anything else, let me just say that no one should accuse Nietzsche of having been an anti-Semite (not in his latter days anyway). He wasn’t a Germanic Nationalist or a political fanatic of any stripe. None of his works can be fairly described as training manuals for the final solutions or for a Third Reich. He was an unapologetic elitist, but this is a far cry from genocide-enabler. All those accusations fall flat.

But he was in many ways a philosophical goon; an irrationalist fawner of nature, of higher crudeness, gregariousness and virility through and through. For Nietzsche, the unadventurous life is not worth lionizing. It's still worth starting though. Just Do It from a literary virtuoso. Perhaps there’s much worse than Nietzsche out there if we’re talking the annals of Anglo and Anglo-translated philosophy, but I can’t think of anyone (who has nearly as many admirers), so he's the springboard for me.

His adventurism distinguishes itself from common natalism in its elitism. A natalist acts out procreation and parenthood as personal projects, without contemplating the details and likelihoods of unimproved futures, or deteriorated grim futures; the faraway ones. A natalist will as a rule procreate or promote procreation with modest or subjective or local aims in mind. The family, community, country and legacy are the objects of focus. Everything beyond this might as well be derivative at best. The time-honoured natalist is a local natalist. I venture the number of Global Natalists who have cropped up throughout history matches the number of Global Pro-Mortalists. Slim to none.

The adventurist isn't so quick to localize and relativize bearers of value. A Bangladeshi life marked by amor fati is just as good as the next door neighbour's amor fati fuelled one, per adventurism.

The adventurist isn't so quick to localize and relativize bearers of value. A Bangladeshi life marked by amor fati is just as good as the next door neighbour's amor fati fuelled one, per adventurism.

Another sharp distinction: Many natalists do not callously dismiss or downplay the badness of tragic lives with a “So What” or with something to that effect. Most of us have known, have been related to, or have maybe even befriended people with natalist beliefs and leanings. If your dealings with them are anything like mine, you won’t quibble when I depict the majority of them as caring people who candidly mourn the banes of existence. Some are more deeply contrite than others, and arguably more than I manage to be on my most contrite days. Some go so far as to take offense when terms like “collateral damage” are used as shorthand for “statistically inevitable existential tragedies”. It is a commendable grief and protest. But it’s also one that should be praised ambivalently rather than enthusiastically, because they do stop short of having the acknowledged downsides override what they sense to be justifiably good about other features of their beloved pale blue dot. They are exculpatory about the dot and ultimately hostile to the proposal of a lifeless tomorrow, but in ways markedly different from the view I hope to precisify here.

But there I go again, gradually shifting the focus onto the moral characteristics of the espouser, after promising that all of that will have to wait.

Many of these people won't ever crack open a book out of non-monetary or non-status motives, much less a philosophical book, so they're hardly opponents in the proper sense. But at least some regular joes will embark on a philosophical mission at some point in their lives. Many will read FN and walk away unimpressed or unconvinced on the substance end of things. They will then read one or more of the Twentieth Century’s pluralists and come away impressed or convinced. The non-adventuristic aspirational pluralist is born this way.

The problem is, the pluralism is just that; aspirational. Hollow on one side. It’s non-hollow for the attention it pays to the upside; the good life is no reductive matter. It is with the downsides that it turns un-pluralistic. These non-adventurists, then, merely take their cues from the masters (the pluralists I listed near the top), meaning they have painted themselves into the same corner. The formidable foe, the non-slippery foe, is thus the adventurist only.

[Post to be completed soon. I really want the published date to be February and not March (don't ask), so I'm posting it now in its incomplete state. This is totally fine because it's hellishly long as it is and no one is going to get this far anytime soon anyway, unless you scroll all the way to the bottom as soon as you open it just to see what's here, in which case; what the hell is wrong with you?! Anyway, I've been writing/revising a bunch over the last week and I still couldn't get this finished. I really suck at completing stuff. Luckily, any deadline I ever have to meet is a 100% self-imposed one, unless you count showing up to work on time a deadline.]

Follow Up To: Constraints On Procreative Wrongness

[1/3]

ReplyDeleteMy thought while getting ready to read this: "I better include the comment section when I send this to my Kindle (comments are normally omitted by default)". It's been 5 weeks since you posted this, and there's nothing. Are you at all surprised by the lack of comments, or do you not expect much feedback on dense subjects of this sort?

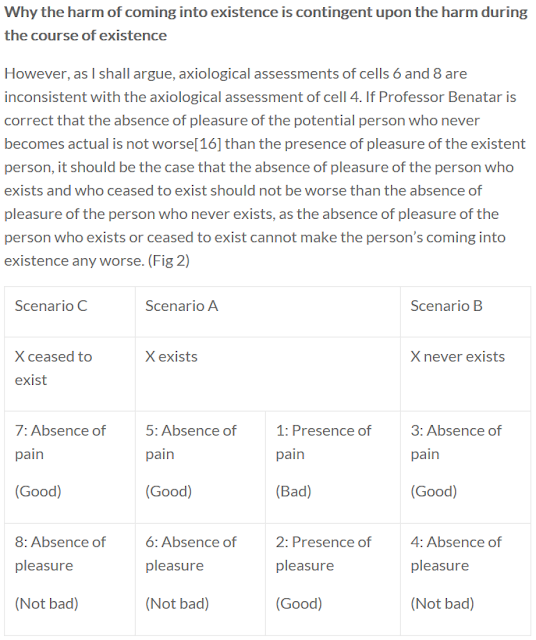

This will be one of those comments when I pick on 1% of your post. Given that it's so narrow and you have bigger fish to fry, don't let it thwart your progress on the trilogy. In short, I'm curious to see you elaborate some more on the Jiwoon Hwang's example. He has an asymmetry of his own (henceforth, JHA). You covered it really briefly, and I get that you two share the conclusion is that David Benatar's Asymmetry (DBA) collapses into pro-mortalism, but what do you think about Hwang's argument, and what makes it so convincing for you? Furthermore, can you clarify where you currently stand on some (or all) of the quadrants (or octants, to be annoyingly pedantic) in those tables?

Here's where I'm currently leaning:

Scenario A (X exists):

[1] Pain = Bad (100% confidence)

[2] Pleasure = Good (80% confidence)

[5] No Pain = Good (100% confidence)

[6] No Pleasure = Bad (80% confidence)

Scenario B (X never exists):

[3] No Pain = Good (51% confidence)

[4] No Pleasure = Not Bad (95% confidence)

Scenario C (X dies):

[7] No More Pain = Good (95% confidence)

[8] No More Pleasure = Bad (70% confidence)

Inferences (all bidirectional/equivalences):

[1] iff [5] (100% confidence)

[2] iff [6] (100% confidence)

[1] iff [7] (95% confidence)

[2] iff [8] (70% confidence)

So, basically I think something like DBA is more plausible than any alternative view I'm aware of. It's only marginally better, because there are bullets everywhere you look in population axiology. I don't believe you and I will disagree on anything other than [3], but I'm not sure, so let me quickly run over them to clear any doubts.

Do you object to my views on 5 and 6? These are highly obvious to me (same ballpark as 1, 2, and 4), and come to think of it, I think that assertions that 1===5 and 2===6 are infallible. If pain is bad for me (or any actual, existing person), then and only then not being in pain must be good (to the same extent that the pain is bad). And if pleasure is good for them, then how can not having the pleasure not be bad? I can ponder and tolerate many asymmetries, but Hwang's view on [6], given his view on [2], is just a contradiction. Think of it this way: adding pleasure makes one's life go better, but taking pleasure away doesn't make it go worse? What?

Slightly more controversial are points 7 and 8. 7 is easier: if I'm in a lot of (non-outweighed) pain and want to end my life, ending it is good for me, despite my no-longer-existence. If this doesn't sound immediately true, perhaps non-agential examples will be more convincing for you. Imagine a dog that is in a lot of pain (and no pleasure): is it better for the dog to be put out of its misery ASAP? (Don't answer: that's a rhetorical question). We wouldn't stupidly stand around the squealing dog and ruminate "but for whom will it be good when the dog dies"? We would make the (only!) correct inference: if a state of affairs is bad for X, then ending that state of affairs is good for X. JHA is on board with that. So far, so good.

But in that case, why the weird verdict on [8]? Ending bad states of affairs is good for people who endure them, but ending good states of affairs is NOT bad for people who enjoy them? That's what JHA posits. Again, I anticipate we're on the same page here too, because you're not a pro-mortalist, and you draw the line between possible and actual people, not between dead and living people. I'm just pointing out how contradictory JHA is, which is a red flag for using it against DBA.

[2/3]

DeleteI'll address one of Hwang's arguments now. It boils down to several intuition pumps, which is fair game (that's how philosophers get off), but it had little impact on me. How about you?

Intuition 1:

1. Life of X has 15 units of pleasure and 5 units of pain.

2. Life of Y has 70 units of pleasure and 50 units of pain.

3. DBA asserts that X is harmed by birth less than Y is.

4. DBA asserts that X is harmed by death more than Y is.

5. ... (Implied premise)

C. So, DBA is inconsistent.

Intuition 2:

1. Life of C has no pleasure or pain.

2. Life of D has 100 units of pleasure and 10 units of pain.

3. DBA asserts that only D is harmed by birth.

4. DBA asserts that only D is harmed by death.

5. ... (Implied premise)

C. So, DBA is inconsistent.

The implied premise in both cases is roughly that the value of death is inversely proportional to the value of birth. But doesn't this beg the question against DB, who accepts and extensively defends that someone can be harmed both by birth and by death?

Deeply imperfect analogy: it's possible to be harmed both by getting into a relationship in the first place AND by breaking up. Just because a situation is better avoided, doesn't mean it is better ended. I think it's perfectly coherent to 1) wish one was never born and 2) not have any inclination to kill oneself, both on purely hedonic grounds.

Anyway, if I have to choose either to kill C or D, I would (probably) be more reluctant to kill D, since I agree that D is harmed more by death, despite also being more harmed by birth. What about you? Should C or D die? Also, does this make one a non-negative consequentialist?

Upon reflection, I'm no longer sure how I feel about X and Y. Being born into a life with more bads is clearly worse for Y, but because Y's life has a lot more good compared to bad, it makes me feel worse about ending it. It might be the ratio of good to bad that I care about for existing lives, rather than the absolute difference tho. For potential lives, it's absolute disvalue that seems to matter. I'm sort of confused now. Where do you stand on X and Y? Who is more harmed by being born, and who is more harmed by dying? This comment is a lot less confident than it was in the beginning. But I've already spent a few hours on it, so I might as well continue. It becomes more certain towards the end.

I am pretty sure that only potential bads should be considered when it comes to procreation, but goods and bads should be weighed when it comes to end of life. Do you disagree?

[3/4] I'll now give my best shot addressing a concern you've expressed a few times over [3].

DeleteInfinite Cosmic Value Floating Around In Space Objection: Point taken, but (bear with me) is it really so terrible to bite the bullet and agree that yes, it's good, and not merely OK, whenever a life containing pain could have been created, but is not created? I suppose it's kind of weird once you've internalized uncompromising person-affecting ethics and actualism, but I feel quite good for preventing existence of people and animals who would otherwise come to exist and be tortured. Is it completely unreasonable to see it as good (and not just neutral) that e.g. there are no more habitable planets in the solar system, and that the messed up evolutionary processes didn't occur on all the places they could've occurred? Because I think that's a pretty good thing. But we don't have to go that far: why is it good to phase out factory farming? It'll be good, first and foremost, because billions of animals will not actualize.

How good it is that a potential being didn't come into existence depends on 1) how bad its life would've been and 2) how likely its existence was, or how close the possible world where that being exists, is. This justifies feeling better about near hits (or near misses?) than about ridiculous and outlandish (yet still possible) bad things that could've happened but didn't.

Still, I'm forced to accept the reductio: that the universe has overwhelmingly more good than bad. I admit that sounds wrong, but (!) only if you pay attention to it and treat that fact seriously. Here's my response; make what you want of it. Suppose it has more good than bad; So what? It sounds crazy because we are not tuned to care for it. We are problem solvers, or at least problem-focused, especially those of us who are negative-leaning. We simply don't care that e.g. child-non-mortality is 95%, or that non-homeless rate is 98%, or that non-abject-poverty rate is 90%. (figures are made up). That's just the wrong thing to focus on (but someone I was arguing with seriously brought up the 98% survival rate of COVID-19 as a thing to feel good about). Anyway, the point is that we only do (and should!) care about the 5%, the 2%, and the 10%, because those are the victims who ought to be helped. The ones who don't need to be helped are real, and it's good that they don't need help, but those good things are at best irrelevant and at worse misleading. As long as there are shitty things happening to even just one person, we are quite happy to ignore the relatively well-off majorities on Earth. Similarly, we could acknowledge that the universe could've been a literal hell for astronomically large numbers of beings, and yes - it is very good that those beings weren't created and tortured - but it should have zero impact on our behavior and decision making. There.

Furthermore, note that "more good than bad" is not the same as "it's better than it exists than if it didn't". In fact, it would be better if it didn't exist precisely because all the beings who were actually badly harmed, would've remained possible and never actualized.

[4/4]

DeleteI think of this view as not just compatible with, but as a kind of person-affecting ethics (albeit, non-actualist PAF), because the person is still at the center of my concern. It's just that I extend my concern to possible persons, and only in respect to bads. I've accepted the weird implications, and I take the hit. But as you're well aware, it's hard/impossible to avoid all bullets in population ethics, and I picked this one because it seems slightly less crazy than the other ones, hence the 51% confidence. So now it's your turn. I'm genuinely curious how you can compare worlds with different beings. That's my biggest concern. Give me a satisfactory answer, and I'll happily renounce DBA. It's just paralyzing, if you ask me. Take a simple example: I remember a brief segment of a conversation you once had with Theoretical Artist. You said that for him, evolution is the best thing that ever happened, whereas you think it's the worst thing. Let's call our world W1. Imagine W2: a world just like ours, except evolution didn't happen there. Can you tell me exactly how you can make a judgment that W2 is preferable to W1, without mentioning possible people? For whom is it better? I can easily explain why W2 is preferable: it's better for the billions of humans and animals that could've been created in it (are merely possible in respect to W2), but didn't get created, and therefore didn't have to live bad lives.

[5/5]

DeleteGoddamit, I messed up Intuition 1. Let me rephrase premises 3 and 4:

3. DBA asserts that Y is harmed by birth MORE than X is.

4. DBA asserts that Y is harmed by death MORE than X is.

Basically JH can't imagine how Y's coming into existence AND death be worse than X's coming into existence and death. I, on the other hand, can imagine it very easily: Y simply has more at stake in terms of both the good and the bad. Only the bad should be considered when deciding whether to create Y. Both the good and the bad are weighed when deciding whether to terminate Y.

One yet another imperfect analogy could be to think of X as a depressed genius, and of Y as someone basic and mediocre who is never quite happy or sad, sort of like a vegetable. It's obviously a bigger tragedy for the genius to be born than for the basic human (because the genius is going to be depressed). But, just as obvious (to me) is that it'll be a bigger tragedy for the genius to die (because he's got good days that by hypothesis outweigh the bad days, whereas the basic human has nothing of value to lose or gain by living or dying). At least that makes sense to me.

Sorry for the delay. Expect for this round of comments to fall short of a thoroughly satisfactory response. I won’t be rereading or quoting you line-by-line, for fear that it will take me days (literally) to wrap things up if I were to go about things that way. There’s lots to cover here, and I can only address it in incomplete doses, apparently, so look for another round of replies from me in the future which will hopefully attend to what I will knowingly omit here (unless you reply to this round in the meantime and I get too discombobulated by those replies to bother with the earlier stuff). FYI though: I’ve read your comments about 6 or 7 times, but the last time I went through them in their entirety and concentrated on them adequately, was at the tail end of April.

DeleteSo first, I need you to confirm or re-confirm that you’re not a modal realist. Belief in modal realism seems a requirement for the class of objections you’ve put together to pan out and pose a threat to my idea of a good/bad symmetry. I don’t know whether, or how exactly, my belief in modal irrealism prevents me from advancing the pre-moral symmetric view, which is something that you subtly (?) suggested might be a problem for me (if I’m reading you right).

If we can agree on modal irrealism, all of the (admittedly mentally draining) problems you’ve brought up should seem conceptually confused right out of the gate. Surely we can believe that our world, the actual world, call it World A, is evaluatively worse compared to a purely hypothetical World B where no one exists. We can do this without considering the possible persons within World B to be actual moral patients in any spatiotemporal or non-spatiotempral sense, and this because World B is a non-entity and represents absolutely nothing. Nothing, as in; not a thing. World B doesn’t exist apart from our schemata, and therefore houses zero moral patients (potential or actual).

Rather than asking “for whom is World B better” we can simply ask “for whom is World A worse” or “for whom is World A bad” or “For whom is World A good” or “For whom is World A evenly good/bad” and so on. And we know for whom; the only beings we can sensibly call moral patients. And those, according to me, are the presently-existing-persons and definitive-future-persons who will exist in the actual world or actual worlds. When I posit a possible person being born and suffering horribly in non-actual World Y, versus possible persons never being born and never suffering in non-actual World Z, this doesn’t make anything better or worse in any reality that I operate within. Comparing actual and non-actual worlds doesn’t compromise the soundness of, to quote from the post: “tethering the goodness and badness of how individual lives actually go with the goodness and badness of what it meant for those lives to have come into existence and what it would mean for them to prematurely end.”

If this is me annoyingly stating the obvious, apologies, but I’ve been writing and rewriting this reply for a while now, and whenever I do my best to not bring up the distracting role of modality, while trying to address your objections anyway, I catch myself gawking blankly at the screen for what feels like hours and inevitably muttering “Just hammer the modality of it all!”.

Ugh, I’m hating how this rendition of the reply is turning out so far...

Here’s some of what I wrote before I started pouncing on modality:

DeleteSo there are two distinct asymmetries to keep an eye on here. There’s the morally relevant one (Hermann Vetter’s example from the post). Then there’s the pre-moral one, for potential persons, with badness counting for everything and goodness counting for nothing, which is the one that doesn’t hold water for me. In fact, this can’t even be called a “procreative asymmetry” as there are no procreation candidates necessary for it to go into full-swing. But for the sharply deontic situations, aka the very situations most ethicists and all observers will have in mind, the asymmetry will be more than obvious (especially when it’s aimed at similarly-situated procreative deliberators). This, and only this, is what’s entailed by talks of procreative symmetries/asymmetries.

Things turn unintelligible once you eject procreation candidates from your evaluative scoreboard, which is an unavoidable part of the equation in discussions that target broadly existential inventories like population ethics. I take it as plentifully more spurious than any bullet that the pre-moral symmetry-espouser is forced to bite. Try doing your best to truly “zoom out” when you consider the interests of potential non-actual people. When I do this, I am left with the impression that any conceptualization of a pre-moral, existential asymmetry feeds on the obviousness of the uncontroversial morally commanding asymmetry. It is a sneaky interaction; illusively powered by the vestige of some type of act-evaluation that’s hard to block-out or downplay, probably because we’re a social species and moral judgment had been evolutionarily drilled into us, as well as culturally drilled in from an early age. I suspect that you, DB and co. are overlooking this interaction between the pre-moral and acutely moral dimensions when positing some perfectly stably lifeless state of affairs and attributing to it an intrinsic plus.

Your first example has “act” written all over it. Quoting you: “but I feel quite good for preventing existence of people and animals who would otherwise come to exist and be tortured. Is it completely unreasonable to see it as good (and not just neutral)” Whether intentional or not, the phrasing “preventing the existence of” will have readers picturing a moral agent who does something for someone else’s sake; in this case a merely possible moral patient. But the intrinsic value does not accrue to the merely possible person, but rather to the beneficent act that is performed in actuality. Acts preventing an otherwise definite harm or definite risk-exposure are intrinsically good acts – irrespective of the non-actual status of the moral patient – but this is explained by the fact that a moral agent is already there serving as your frame of reference for moral value, whereas the barrenness of Jupiter offers you nothing in the way of agent-referential bootstraps. This complicates (or perhaps overthrows) the person-affecting restriction, and I'm not going to delve into that in this round, because there's no way to cover it without omitting even more of what you brought up.

More needs to be said about the (largely psychologically steered) interaction between pre-moral bearers of value/disvalue and the plainly moral ones, in part so as to get a grip on the deontic status of deliberately preventive acts vs. incidentally (amorally) preventive acts. The former class of acts involve a moral agent who is repulsed by the process of her abortion, but who nontheless self-sacrifices and chooses to abort for the sake of the unborn child on risk-averse grounds. The latter class involves having a wank into a hanky. One is clearly beneficent, the other should not bizarrely be viewed as beneficence-on-steroids. And we don’t need to cover any of that in depth right now. The fact that philosophers know to delineate moral value attributions between these two types of acts suggests that there is something wrong with a potentiality-driven, categorically-binding good<bad asymmetry.

My struggling to answer (or even decipher, frankly) some of your questions is arguably a bullet that I’m taking, especially if I’m mistaken about your reliance on modal realism. Fair enough. But are you really so sure that the bullets I’ve bitten in the post are more wounding to my conclusion than the ones you’re prepared to bite have been to your conclusion? I mean, I have questions too:

DeleteDoes the good<bad pre-moral asymmetry leave anti-natalist advocacy in the awkward position of being indistinguishable from utopianism? I have an easy time explaining why anti-natalist advocacy has nothing to do with utopia-mongering; all results are non-positive. How does someone who views the mere absence of intrinsic bads as intrinsically good get around this? Or is “Yup, anti-natalist advocacy is another example of people trying to usher in a utopia” one more “slightly less crazy” bullet you’re willing to bite?

But even this is getting ahead of the curve, as we’re far from a dystopia anyway, and always have been.

Relatedly, if the pre-moral asymmetry is true, is it accompanied by a fact of the matter regarding “how much” non-instrumental value emerges from all the relevant intrinsic-value-designators? If yes, is it beyond comprehension?

Does the quantity of absence-based non-instrumental goodness increase from one moment to the next, as it clearly does with suffering? If so, saying that the intrinsic good dwarfs the intrinsic bad seems like the greatest understatement of all time. When you land on something in the neighbourhood of “the greatest understatement of all time”, how is this “slightly less crazy” than the alternative?

Equally worth pondering: How life-prone do the “conditions necessary for life” have to be for something in the cosmos to shift from neutral to good/ To qualify as an absence-of-bad based value-designator? Or is it an “anything goes” type deal? Are Black Holes every bit as value-rich as barren lands are presumably taken to be? I suppose water-rich planets would produce more absence-based goodness than dry planets. Ditto with carbon and so forth.

This is worth noting even for potential earthlings, just recall the tirelessly quoted Dawkins passage explaining how many possible people could exist thanks to the structure of our DNA, but who remain unborn. So present-day earth, too, would easily qualify for “more good than bad” and by incalculable amounts. Yeah, I find this crazier than what I’m trying to get at with the pre-moral symmetry.

Yeah, lots of questions there, but they’re interrelated so you can forgive me.

Even if it turns out that there is something non-instrumentally good about the (incalculable?) vastness of lifelessness, appreciation of this fact will have to be non-identical to the intrinsic good of a life well lived, aka the immunity-rich life of someone like Joanne Cameron. It’s arguably not even similar to it. It would be so odd to deny that the best hour of an incredibly lucky person’s life is a quantitative category of intrinsic value that doesn’t lend itself to being outweighed by a sufficiently spacious or lengthy absence of an intrinsic bad manifesting.

It would seem that whatever is (speculatively) non-instrumentally good about the absence of intrinsic bads, will only be good in a non-quantitative sense. If you believe in aggregative theories of value and disvalue, the next move is to say “and therefore in a non-intrinsic sense”. Modal realism is one way of objecting to this… and I’ve said all I’m going to say about that flavour of philosophical eccentricity early on in this post. (and surely you don’t believe that this is what’s ultimately fatal to the pre-moral symmetry; my belief in the literal nonexistence of possible “nearby” worlds…)

So if absence-based goods are non-quantifiable, we have every reason to doubt that they are intrinsic goods proper, unless we take the traditional absolutist view that says intrinsic value and disvalue is also a non-quantitative property, which I’m not about to do.

ReplyDeleteAdditionally, are we subdividing potential persons along i.e. uniquely realizable lines or non-uniquely realizable lines?

Your question on who should die: X vs. Y:

The sufferer should die. Since X avoids the positives and the negatives from womb to tomb, X is strictly speaking not a sufferer due to having been and remaining alive.

Y doesn’t avoid some negatives, so I pick him to die.

Now maybe Y doesn’t quite qualify for “sufferer” status despite his encounters with some negatives. What is “-10” here? Discontentment? Hellishness? Can you give a description of the worst thing that Y has had to endure, or the worst thing he stands to endure by remaining alive? If relatively unpleasant experiences like exhaustion or soreness after a gruelling labor-intensive shift characterize the negatives of Y’s life, then the non-negative consequentialist answer you mentioned will definitely be tempting for me.

It's been something like seven years since I've last presented negative consequentialist views to be "exceptionless" moral mandates. I believe everyone should "round off" to some type of NU, with the strength of the rounding effect being proportional to the absolute level of intense suffering the moral agent is in a position to offset.

This shouldn’t really be a surprise, considering all the promotion that lexical-threshold inferiority views have received on here. If we (briefly) set aside issues of volition and coercion, and evaluate harms and benefits directly from the standpoint of Y’s valences, it makes sense to extend the inferiority-attentiveness I’ve championed (and which you’ve never objected to, as far as I recall) over to a superiority-attentiveness that exists on the other end of the spectrum. Personally, if I were facing a choice between a enjoying a mediocre or slightly-above average longevity culminating in a death at 90/95, versus living out the best year I can possibly have and dying immediately after the clock strikes midnight at the end of day 365, I would choose the lexical-superiority year over the merely decent longevity. (On the stipulation that no one is left to grieve my early death, and that I wouldn’t be improving the world by sticking around, and stuff like that)

I don’t know if research in social or cognitive psychology backs up this sort of pro lexical-superiority choice to the point where I am justified in generalizing its soundness and incorporating it at the level of applied ethics without running into objections. From what I recall in a paper I read years ago, it's nearly universally applicable when we turn to (something akin to) lexical-inferiority. Subjects pass on the short term intense pain slice and opt for the much longer, milder, overall-higher-tallied pain slice. But I have no clue if the same holds for experiments looking at what subjects choose when one of the options is something akin to lexical-superiority.

Clearly, such findings should have some implication for so-called exceptionless moral theories.

Quick addendum.

DeleteI guess it has been too long since I last revisited BNTHB or Benatar's subsequent writings where he further explores and defends his asymmetry. I say this because I recently watched a long form interview with Benatar on the Cosmic Skeptic's podcast where he offhandedly mentions that his idea of an absence-derived good is, in fact, a non-intrinsic category of goodness after all. How about that.

If you're interested, here's the video: https://youtu.be/ez68B4Np9rc

He doesn't refer to it as an instrumental category of goodness, though. He dubs it a 'comparative' type of goodness. This is a shoddy move because the remaining quadrants (surely the "Presence Of Pleasure" and "Presence of Pain" ones, at least) refer to intrinsic goods and bads and more importantly, the four quadrants are meant to play off of each other in categorically consistent ways. Their conjoined interaction is what's supposed to make the broader point about asymmetric realities truly land for Benatar. So much for that.

So my question is; how is this not sophistry? Set up a basis for comparison that you have every reason in the world to predict will be construed by readers as comparing like with like, then drop a reminder here and there (towards the tail end of this particular interview) that we are not, in fact, comparing like with like. We are actually comparing strictly intrinsic goods/bads with each other, and also with strictly comparative goods (non-instrumental goods?) too. How much comparative goodness outweighs non-comparative/intrinsic *anything*? How do you begin to answer a query like this? If these types of questions were meant to be left hanging in the air, or are in principle unanswerable, then I'm tempted to reiterate my earlier concern; why care about non-intrinsic goodness? Updated version: Why care about comparative goodness? Why overcomplicate the quadrants by setting up an apples/oranges comparison?

Why it matters: Anti-natalists on YouTube parade around their copies of BNTHB similarly to how devout theists parade around their holy texts. Despite 14 years to latch on to the (potentially included) passage in BNTHB that stipulates the presence-derived good as an apple and the absence-derived good as an orange, none of those people will grasp it. They are evidently primed by the book's general tenor to treat the absence-derived "orange" good as superior to the Joanne Cameron life "apple" good. Even you, here, were prepared to bite a bullet this whacky because all the alternatives are somehow worse.

Additionally, I just reread my four replies to you and (OTHER THAN THE TEMPTATION TO DELETE THE ONES CONTAINING TYPOS) I noticed that I put polite pressure on you not to reply in the near future, before going on to pose numerous questions to you that, had someone posed to me following the shush, I would have been rather annoyed. As such, you don't have to wait to reply, if indeed you've been chomping at the bit to reply and didn't because I basically asked you to hold off for a bit. That was unreasonable of me.

I owe you a book length reply on provisionalism and doctrinism, and have been working on putting together some of it, but I'm slowly realizing that a comment section is probably the wrong place for it.

Oh, I'm not holding off my replies because of something you said. Don't worry about that. If I had given your four comments the attention they deserve, I would have replied right away. So I have to confess I didn't get to them yet, beyond a quick skim. I tell myself that I really just want to savor the subject, and so I'm waiting for a distraction-free window. I've been doing this with your 4-5 blog posts that I still haven't read. But more honestly, these are dense topics and by the time you responded, my motivation was elsewhere. But it's right there on my list, which, just a reminder, you can see and track on that correspondence checklist I shared with you the other day. It's interesting that for me, the procrastination pattern is "wait->wait->wait->read->respond", whereas for you it's more like "read->wait->wait->wait->respond". I was hoping to invest my next window into the Cops and Race video and the associated community post, as it's more of a current issue. But if this, or any other thread, is more important, let me know and I'll reprioritize.

DeleteBy all means, pour all of that energy into the Cops And Race video and the stuff I wrote about it over on Community. Eagerly anticipating to hear from you. Much less "Am I missing something? I'm probably missing something!" fears from me when it comes to all that, compared to all of this, and I could use some fearless posting and responding right now. Plus it's kind of hard to ignore an Empire being set ablaze and crumbling, however slowly, before our very eyes.

Delete"It's interesting that for me, the procrastination pattern is "wait->wait->wait->read->respond", whereas for you it's more like "read->wait->wait->wait->respond"."

I have a pattern?

"you can see and track on that correspondence checklist I shared with you the other day"

I will take a closer look at all that. I don't cozy up to new sites as quickly as the average person does, so I just glanced at it and navigated away before the feeling of being overwhelmed by it kicked in. And knowing me, it would have kicked in. (Openness to change, site diversity, having more than a few accounts to keep tabs on... all objectively evil.)

But also save that Cosmic Skeptic podcast so you can listen to it sometime in the future if your apartment is still in good standing and not burned down by then.

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDelete"I have a pattern?"

ReplyDeleteYou sometimes respond and mention reading the post you're responding to several weeks ago. But now that I think of it, this only happened 2 or 3 times, so it might've caught my attention not because you do it a lot, but because it's uncommon.

"if your apartment is still in good standing and not burned down by then."

Oh crap, is it that bad? I haven't been following the news much, because of a weird (and somewhat contradictory) mix of apathy, annoyance, and worry that fuel one other. I used to think a destabilizing event like that would be interesting and fascinating. But now that it's happening, I feel equal amounts of apathetic, annoyed, and worried. But it might be exaggerated in the media. I go outside quite often, including downtown, and everything looks like business as usual to me.

fuel one another*

DeleteAnd btw, you don't need an account. The document is viewable and editable as long as you have the link to it.

Borgata Hotel Casino & Spa, Atlantic City, NJ - CasinoBonusBonus

ReplyDeleteBorgata Hotel Casino 텐뱃 & 있는 Spa Casino & 토토커뮤니티 Spa is a luxury resort casino and hotel bet located on the waterfront in Atlantic City, New Jersey, on the Rating: 4.1 · 4 커뮤니티 사이트 votes