Due to the enormity and distinctiveness of contentious issues, it is improbable that the fabric of political issues would be understood as ideologically combinational in the eyes of an omniprecipient being. Orthodox versions of political nihilism recognize this, only to posit that such a being would do away with all systems and ideologies in equal rungs and never look back.

Political pragmatism, as I have sculpted it, makes note of the same, but posits an omniprecipient being who urges political thinkers to perish the thought of doing away with all systems and ideologies in equal rungs. Instead, the kosher pragmatist pictures the masterly spectator as one who declines enough of the essential ingredients from all systems and ideologies. Pinpointing where the "enough" mark sits is an empirical question. This doesn't make it an easy one. The point is, declining enough ideologically essential ingredients leaves the kosher pragmatist appearing politically outlandish to onlookers with principled sensibilities.

Though political nihilists and political pragmatists occupy the same neighborhood, it is a spacey neighborhood. Their home streets are located on the opposite ends of the district, and are nothing alike architecturally.

/Summary

Worldviews And Narratives

Stealth algorithms shape people's ideologies. Opportunistic grifters distort and oversimplify otherwise useful taxonomies. Scholars avoid the mud for fear of letting the mud-lover drag them down to a level they feel zero obligation to entertain, even if their concerns reduce to optics. It's hard to overstate the toll this has taken on Socratic discourse. I'm out of the loop enough to know that I can't really speak to whether observations like these amount to truisms just yet.

Take the algorithm observation. Is it a truism? If not, the minority speaking out against the pervasiveness of algorithm deployment needs to get (much) louder. If yes, I have to think it's the sort of truism that's blocked out as a matter of routine. Users acknowledge the reality of micro-targeting for commerce purposes, and its gradual takeover of spaces previously reserved for dialectic purposes. Users nod, and leave fist-shaky comments saying something really ought to be done about this. Said users, then, go about their ordinary digital media business as if they're not a part of the solution from the bottom-up.

Nothing groundbreaking there. Unknown comedians become household names by incorporating into their acts church-goers who, not long after liturgy wraps up, block out the teachings they claim to have attended church for in the first place. You can say that there's a certain banality to pointing out that church is a meme in 2019, and is unworthy of serious scrutiny, but over one billion dollars has been raised to rebuild Notre Dame as of my writing this. Some truism.

Similarly, the truism that so many convictions are algorithmically acquired and (especially) algorithmically reinforced, ends up as forgotten knowledge. For the church-goer, abandonment occurs when temptation comes knocking. For the algorithmic ideology preserver, it occurs when culture clashes come knocking.

With this, the reason "ideologue" ought to be a term of abuse is not because it connotes extremism or pushiness, but because today's ideologue is first and foremost a narrativity seeker. A compulsive connector of ideological tenets which, properly understood, are ultimately disparate. Was it always like this? Scantly, maybe. I don't see it being the norm prior to expansive storytelling through cinema, literature, and other types of fiction protagonizing matters.

Either way, the digitization of media was the nail in the coffin.

Aspirations to content-connectivity aren't a spectacularly new thing. What's newish is the scale and number of speakers captured by self-expression, shared struggle, life-stories, redemptive purview, the idealization of political belief as a holistic puzzle with fitting vs. unfitting pieces. Taking a principled stand in favor of A and B, and one against C and D, and holding that there is a relational goodness between A and B and a relational badness between C and D such that the desiderata for "A/B > C/D" is combinatory. Add in wild-cards like absolutism and universalism –– making the desiderata insertable across all situations and populations –– and it becomes harder to maintain a positive view of compromise even when alternatives to compromise look grimly risky. Or in the rare case where a bargain is the closest thing we have to Pareto optimality.

For a worldview to be one step ahead of algorithmic gamesmanship, it needs to promote visceral feelings of disgust at the sight of, for example, remorseless dog-piling, no matter the crew that's doing it. Equally welcomed are visceral feelings of disgust at seeing any out-group's weakest links repeatedly targeted by cleverer actors. I'm not seeing such disgust expressed anywhere, truism or not. (I am seeing sanctimonious pleads for all decent people to try and get along, and that's besides the point, as explained in Part 1.)

For a political program to be ideologically apathetic to concatenations in contents, it would need to be hyper-heterodox, its aficionados wise to the mountingly subtler mechanics of narrative inculcation. A heterodoxy within heterodox quarters, but without the nauseating self-congratulatory pats for "thinking outside the box that's outside the box". Or at least, with aficionados putting in tons of effort to subject any such prideful feels to self-deprecation, should they ever arise (they will).

Experience teaches that candidates for this "turbo" heterodoxy cannot be screened via raw intellect, credentialism, or even moral uprightness. If only it were that simple. By and large, the best candidates are volitional and semi-volitional solitaries who, for whatever reason, find and maintain solace in spending inordinate amounts of time by themselves. Something about habituating to this slowness leaves you unmoved by the allure of sociability, solidarity, fraternity, camaraderie and other aspects of interpersonal gain.

Over time, the people who are moved by the promise of such gains, and who substitute their simpler manifestations for sophisticated political ones, become easy for the loner to spot. Once spotted, the giddiness, cliquishness and general predictability they bring to the table just grates on you. Their duplicitous construals and portrayals of mundane things, like anger –– noble when the source is my crew, pathological when not –– just grates on you. They are not to be stomached, regardless of their actual moral character, ethical behavior, pro/nay attitudes, political stances, and precise shade-of-frenemy status.

On the other hand, you could just as easily, and in the spirit of pragmatism, retort with a boohoo and a who's got time for that? Rivals abound, and they're packing connectivity under the guise of coherence via C-to-D relata. They're also practiced in persuading fence-sitters by generating curated social media activities. Better amp up that A-to-B relata and curated social media activities of your own, lest you be outdone. Out-influence the influencers, by hook or by crook, and do it quickly, in the name of pragmatism.

And while this does present something of a bind, it is only so within the confines of a here-and-now, or in the foreseeable near-term. Are we to sell our intellectual and temperamental souls, for a payoff that stops at the near-term? Some payoff. I suppose answers will depend on (1) whether you are naturally a solitary in the first place, (2) whether the non-solitaries' tendencies grate on you the way they do on me, or at all, and finally (3) whether those sculptures of pragmatism by me from earlier resonated with you, and to what extent.

Needless to say, I don't think the relata is worth the price; not for a payoff that binds on the week only, or the month only, or the year, or even a decade.

But this assumes the presence of an official party that's capable of doing even that meager, near-term job. Sometimes, those parties are indeed present. If you're talking about American politics, then yeah, there's a case to be made for "anything but GOP" and this means playing nice with the Dems' relata as a formal coalition. That's just how unsavory the GOP is. But venture beyond the US and pick-your-poison tasks turn dicier. There is no Canadian equivalent of the GOP, making voting, awareness-spreading, and political fundraising too gnarly to bother with, so I don't. It will take an awful lot for that to change.

Not so for the structuralist! Just as nihilism in politics denies that there can be compelling reasons to vote, structuralism asserts that there are always compelling reasons to vote (or almost always, for the less robust structuralist). Participation is seen as a civic duty and is, to one degree or another, even morally praiseworthy. Where the nihilist ridicules this, my kind of pragmatism denies the universalizability of it, and then particularizes it.

Depending on how you do your political zoning, the pragmatist and the structuralist can be as neighborly as the nihilist and the pragmatist can be. [1] By that I mean; some meta-similarities, but typically more meta-dissimilarities.

When I mutter "Take The Grey Pill" to myself, I'm not talking about the Red Pill meeting the Black Pill halfway. I'm also not talking about anything that the users on this weird subreddit are talking about. What I'm trying to get at –– and doing a subpar job despite my overweening tone –– is the need for balance between nihilism and structuralism in meta-politics. And not just on account of the wideness between A and Z as such, seeing as issues A through Z are one piece of the pie. Nay, the inanity of content-connectivity compounds in a world where one alphabet represents but one domain of issues.

By my count, there are nearly 400 alphabets or writing systems. There aren't quite 400 domains of issues and policies, so to keep the analogy alive, I'll narrow things down to nine alphabets. It works on both counts, as over 99% of the actually-used-alphabets in the modern world consist of the following nine:

- 1. Latin

- 2. Greek

- 3. Cyrillic

- 4. Armenian

- 5. Korean

- 6. Hebrew (it's only a pure alphabet when written with vowels)

- 7. Arabic (debatable, as it doesn’t represent all the sounds of every dialect)

- 8. Braille

- 9. Georgian (Mkhedruli)

Let's say that each letter in the Latin alphabet represents a particular stance in the annals of legal theory:

- A = Legal Positivism

- B = Legal Formalism

- C = Legal Skepticism

Each letter in the Greek alphabet represents a particular stance in the annals of monetary theory:

- α = QTM / Quantity theory of money.

- β = MMT / Modern monetary theory.

- γ = Neutrality of money.

Each letter in the Cyrillic alphabet represents a particular stance in the annals of social theory and social science:

- а = Methodological Individualism

- б = Methodological Holism

- в = Conflict Theories (influenced by dialectical materialism)

- г = Social Constructionism

I'll stop there. Most of the letters [unique stances] have been left out. Two thirds of the widely used alphabets [domains of issues] have also been left out. There's scratching the tip of the surface, then there's scratching the tip of the tip, or the tip of the tip of the tip. Invest in a connectable theory of politics and see your mind suffer the connotative burden of yes-true-ally where no-true-ally would've sufficed. Pragmatists don't have to be allyless, just as they don't have to abandon ideology and taxonomy per se. What's needed of us is to take seriously the expansiveness of lettered issues to the point where it stamps out wide-eyed hankerings for connectivity in ideology-formation.

Documentaries/journalists/etc have been revealing how Big Tech's stronghold on digital media contributes to the intensification of A-to-B connectors being pitted against C-to-D connectors. The makers of those docs are not hyper-heterodox. They're the orthodox heterodoxy, from Adam Kokesh to Brett Weinstein. They want to modify the script, not flip it. Brett believes in an unambiguous line separating progressive authoritarians from progressive anti-authoritarians (he gets a pat on the back, having styled himself as a member of the [self-styled] anti-authoritarian prog camp). But how does this authority pro/nay line square with any of the above preliminaries? Suppose you staunchly favor:

- (B) Legal Formalism

- (β) MMT

- (б) Methodological Holism.

Then suppose that four out of five people who also favor those positions run afoul of whatever it is Brett says earns someone the "anti-authoritarian" title. To the extent that you're comfortable identifying as a progressive and feel that Brett suffered an injustice at Evergreen, Brett would urge you to set a good example for progressivism by denouncing authoritarians and uniting with anti-authoritarians. Should you? Should it be a big deal? Should you make it into one? Should (B) (β) (б) take a backseat? If yes, what happens once we run the gambit of positions in the three alphabets and find that nine out of ten authoritarians (per Brett) align with you on most everything else? If yes still, what about when the remaining (two thirds) alphabets are deployed and authoritarians echo your views over anti-authoritarians by an order of 10:1?

You see the issue here: Brett's gripes don't extend to the nodus of connectivity, relational goodness –– i.e. progressive here therefore progressive there –– and the structuralist framework that continually pumps air into it. His complaints can be traced to the difficulties in sustaining A-to-C and A-to-D groupings now that algorithms –– along with some questionable curricula at Evergreen –– inflate groupings along orthodox A-to-B vs. C-to-D lines. Something similar can be said for Kokesh's preferred B-to-C and B-to-D groupings, and how the entrenched C-to-D group elbows out his vision of an enlightened political order. Neither of the two seems concerned with or aware of the impossibilities of having the other alphabets come along to supplement the grand narrative. Same goes for these people, none of whom share my dissatisfaction with the faux-coherence of structuralist mindsets and formulas.

The more unconnected issues you put on the table, the more suited for connectivity they are painted as being by the commentariat and their listening legions. I await the day where Brett, Adam or anyone in the Heterodox Academy says something like: When people bemoan that an issue dear to them has been politicized, what they really mean to bemoan is that said issue has been connectivized.

I probably shouldn't be holding my breath.

Pining for less algorithmic and more creative –– but still artificial –– coalitions-of-necessity can be an improvement, in the short term. In the long run, the harm/benefit paper-trail is impossible to follow, at least if you try to follow it along political lines and legal inputs. [2] This barrier in mind, I don't see how coalitions-of-necessity do us any good at all. They're not helpful with empirically verifiable/falsifiable positions, nor with the purely evaluative ones, nor with the positive/negative judgments –– negative with those who take one different stance too many –– that arguably follow.

Part of me wants to say that you don't need to be a pragmatist to sense the inanity in conferring to connectivity a starring role in pol-theory. Another part hisses as conceding even that much would be unduly kind for a setting like ours where political structuralism is dominant. Once you take everyone who "thinks or talks about politics" into account, it's undeniable that structuralists (idealists, narrativists, holists) heftily outnumber non-structuralists.

Whether through anecdotes or polling data, you know it's vanishingly rare for people to synopsize their political selves by invoking labels like "pragmatist" or "instrumentalist" or "constructivist" or any other antidotes to structuralism.

Rigor Without Structuralism

Political moderates imagine that political moderateness, in content, assists them in resisting fanaticism more ably than the radical ever could. They are mistaken, insofar as they end up absorbing commitments to moderation; another structure-matrix. Though I find the average radical to be more susceptible to narrativity than moderates are on average, I suspect that this would change or flip if moderates started being pressed like they haven't been in decades. We've seen snippets of such pressings on YouTube, with classical liberalism limned as the stockade for keeping out radicalism on all fronts. Those who drove and boarded this train relied less on reasons, and gratuitously on narratives (i.e. lost glory of Western Civ) to make their case. Like clockwork, they skirted all pesky facts about the economic tentacles of classical liberalism being anything but moderate. A perfect distillation of quests for connectivity turning otherwise passable speakers into half-truth spouters.

Where genuine radicals have a knack for overlooking satisfactory policies situated inside the box, genuine moderates unironically mimic them with their own dismissals of satisfactory policies which happen to be outside the box.

My favorite example of radicals snubbing decent enough policies: PPP style arrangements and economics in regions where stability is highly valued and where economic ideology is statically mixed; where there is nothing to indicate that economic beliefs will become heavily unmixed in the near/far future.

My favorite example involving moderates snubbing decent enough policies: The grim prospects of on-demand legalization of euthanasia winning the day.

It cannot be stressed enough that the moderate and the pragmatist are separate political animals. I don't know of any moderates who take a pass on ascribing pol-identities to themselves and to the non-moderates they're alarmed by. Any given pragmatist can be a supporter of immoderate positions, as with the euthanasia mention and my endorsement of it. Just as proceduralism is not a distinct pol-identity in jeopardy of moderate-yay/radical-boo overviews, neither is pragmatism. The chief function of pragmatism should borrow from (the best of) proceduralism while acquiring novelty in its non-absolutist tolerance of majoritarianism; allowing for majoritarian overturnings of (some) policies heretofore believed to be sacred by proceduralists and constitutional purists.

Which policies?

What portion of existing policies is amendable to majoritarian rule, in pragmatism? What portion of the remaining non-majoritarian ones is absolute?

I have some ideas:

Is this a copout? Not by my lights, for pragmatism is a political-operational program for navigating around tireless stalemates and advancing compromise through non-factionalism where factionalism is lumpish. With structuralist models normalized, factionalism is drilled into many people's heads over a lifetime, dramatically and non-analytically. [3] Constituencies are captured by storytelling in the service of splitting, and with elected officials up for reelection, refusals at the state and local level to condemn obstructionism at the congressional level will be standard fare. This hampers sensible non-positional aims and projects. Opportunity costs pile up, bound to be on the backburner.

Here pragmatism swoops in to discourage protagonizing matters and encourages an emphasis on absolute gains over relative gains, following in the footsteps of liberalistic schools of thought in IR. Moderates had a chance to apply this school to domestic contexts, and they blew it. If pragmatists are to make it work, they must, as non-annoyingly as possible, bang the drum of impersonal reasoning; incompleteness and all, fallibility and all-too-human setbacks and all, so long as we set our meta-sights on the categorization of everyone's crucial, important, semi-important and unimportant policy priorities.

How often are you nudged into reflecting on your and everyone else's priority weightings in this way? When was the last time you saw a pol-junky pressured by his allies to ponder "What are the semi-important or unimportant policies I would be content to lose out on, if the upside consisted in a win for that one crucial or merely important policy that I strongly favor?". The answer is "never ago" and this is a heuristic travesty.

Heuristically, everyone should anticipate that the most efficacious policymaking will have ideologically non-cohesive effects, and that this policy-induced fracturing cuts through the arbitrary whims determining what passes for moderateness and radicalness in-the-current-year.

Gay marriage was more radical to arch progressives in the 1950s and 1960s than it is to most arch conservatives today. As temporally hollow as this admittedly pedestrian example renders the radical/moderate split, decade to decade, and the progressive/conservative split, decade to decade, other examples cast equally big clouds on other splits. You know the ones. The all but inevitable improvements we keep hearing about, pledged one-sidedly by propounders of take-your-pick:

- Centralization/Decentralization

- Democratization/Technocratization

- Nationalization/Privatization

- Localization/Globalization.

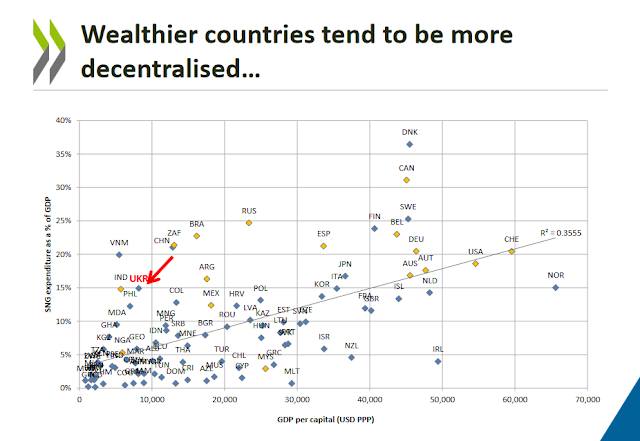

I have a more centralization-friendly history than my pragmatism would let on, so the following is a mini attempt at bridge-building: When I obtained proof of increased decentralization worsening things in Ukraine, I thought to myself "We cannot, even as a hopeful microsecond-long impulse, try to extrapolate anything general from this". For those with a track-record of siding with centralism over decentralism, the temptation to do just that is, if not hard to resist acting on, certainly hard to stamp out altogether. This was the first time that I noticed the "STOP" in myself before the temptation even arose. I believe that I initially read the paper sometime in the summer of 2018, so it took way too long for me to "get there" and actually practice what I've been preaching going back to well before mid 2018.

One reason for not extrapolating anything:

Don't mistake the above graph for an attempt to present a knock-down argument against centralization. Despite updating, I still don't feel comfortable making sweeping statements like "the world needs more decentralization" or the converse. There are undoubtedly more correlative and purely non-causal factors contributing to the trends in this graph than there are purely causal ones –– causal in the sense of economic boons being a direct product of a weakened central gov't. But surely it's not all accidental (not for this former centralist. See also; Scott Alexander's warnings about the One Man Study approach overtaking the minimum wage debate). These findings don't need to be a catchall argument against anything. But they do cast a commendatory light on passivity in the face of data-driven reforms which are ideologically fragmentary, and I'll leave you to fill in the blanks as to why passivity in paradigm-changing situations is slated to slaughter any thinking person's pol-identity.

Within a customarily principled system, an unacceptably high number of cherished crucial policies will be Dead Wrong rather than falling "a jot shy" of being right. Picture there being one thousand policies to bargain with, in total. Of those, one hundred qualify for something approximating "life or death" policies. Of those, ten life-or-death policies turn out to be Dead Wrong a few months after implementation. 9990 other policies facilitated by the same theory –– the majority of which are of lesser salience –– turn out to be spot on a "a jot shy" of spot-on, after implementation. The takeaway is a 10-for-9990 bargain that, while offering a failure/success rate that's numerically impressive, nonetheless fails to stand out.

I don't think I'm alone in saying that polities ought to optimize the "spot on" effect of those fewer life-or-death policies, and get as close to 100/100 as humanly possible, even if doing so entails choosing a scheme that scores nowhere near 900/900 on the lighter-weighted policy front. Being in lockstep with me on this means tolerating innumerable nuisances in the name of avoiding tragedies, regardless of who is spared a tragedy and who is saddled with an excess of nuisances. It would, after all, be an astonishing feat were all nuisances to befall all citizens equally. Of course, it's not just nuisances I'm writing off here. There's plenty in between, and I'm happy to make room for the upper-bound stuff that's technically short of "tragedy" level, but still quite bad. So maybe we're looking at 150 policies as the crucial policies, not just 100. If you're still in lockstep with me, you will have noted that there is no formal political system for us. Time, manpower and resources are in short supply, and from a time/manpower/resources management standpoint, every system currently on the menu ignores or omits my prioritization. From progressive theories to conservative theories to centrist theories; none apply a lexical-superiority to the 100 or so tragedy-averting policies that, yes, I believe majorities would prioritize if asked about it under wide reflective equilibrium.

This is not to say that progressive, conservative and centrist theories manage public time/manpower/resources indiscriminately. They discriminate, just not in the right ways, or anything close. I happily grant that one or another principled system is capable of getting more than a few, and perhaps all, of the less important or unimportant policies perfectly right, whether objectively or according to what the theory internally seeks for adherents and likeminded sympathizers. Of that we should have little doubt. But that's immaterial.

Or, if a single system miraculously succeeds at getting all (or most) of the crucial policies entirely right, on paper, it manages it as an incidental knock-on effect. That is, it will fail to do so for the right reasons. I think reason-responsiveness should be taken into consideration, such that the three core ingredients for grading the success/failure of a system are:

(i) Outcomes-apt

(ii) Methods-apt

(iii) Reasons-apt

All this and more in Part Three!

Coming this May, probably.

Notes:

[1] A further split can be made inside the street containing nothing-but-pragmatists. The split weeds out the meliorists

from the pessimists. If a desire to move out of the nihilist-cohabited neighborhood represents a belief in

progress qua historical directionality, and a desire to stay anywhere near nihilists represents a hostility to the idea of progressive directionality; be it a hostility rooted in epistemic, prudential or ethical concerns, then meliorist pragmatists are pragmatists who want to move and inch closer to a utopia, despite knowing that utopias are not in the cards. Whereas pessimistic pragmatists are pragmatists who want to stay and for whom knowledge about utopias not being in the cards is reason enough for continued neighborliness with nihilists.

[2] The shortfalls of connectivity apply to nonlegal issues, but to a lesser degree. Though nonlegal propositions can be as verdictive as any legal edict, the former enjoy the benefit of not running up against the thorniness of enforcement in the wake of passionate disagreements. And while the category of problems that vex me the most are not of the "to enforce or not to enforce" canon, this doesn't mean that issues surrounding enforcement are to be taken lightly. For one, I haven't reached a forceful conclusion regarding the justifiability of technocratic elites saying "to hell with nudges" and outright constraining a non-negligible number of bad choices of predictably dense people, in their own long-term interest. Papers like this one become more (theoretically) persuasive as time goes on. As for praxis, decision-time is paralyzingly difficult. The shakiness of systems qua theoretical models is at its wobbliest when the system-builder underestimates the complexity of legality/illegality in legal theory, and the potential for ideologies unfamiliar with said complexity to make matters worse.

[3] Psychologically, a part of the problem could also be the lasting-effect of the scarcity mindset. Raghunatan has written extensively about it, though I can't recall if he calls it out specifically in reference to pol:

[2] The shortfalls of connectivity apply to nonlegal issues, but to a lesser degree. Though nonlegal propositions can be as verdictive as any legal edict, the former enjoy the benefit of not running up against the thorniness of enforcement in the wake of passionate disagreements. And while the category of problems that vex me the most are not of the "to enforce or not to enforce" canon, this doesn't mean that issues surrounding enforcement are to be taken lightly. For one, I haven't reached a forceful conclusion regarding the justifiability of technocratic elites saying "to hell with nudges" and outright constraining a non-negligible number of bad choices of predictably dense people, in their own long-term interest. Papers like this one become more (theoretically) persuasive as time goes on. As for praxis, decision-time is paralyzingly difficult. The shakiness of systems qua theoretical models is at its wobbliest when the system-builder underestimates the complexity of legality/illegality in legal theory, and the potential for ideologies unfamiliar with said complexity to make matters worse.

[3] Psychologically, a part of the problem could also be the lasting-effect of the scarcity mindset. Raghunatan has written extensively about it, though I can't recall if he calls it out specifically in reference to pol:

- "If you're caught in a warzone, if you're in a poverty-stricken area, if you're fighting for your survival, if you're in a competitive sport like boxing, the scarcity mindset does play a very important role. Most of us are the products of people who survived in what was for a very, very long time, in our evolution as a species, a scarcity-oriented universe. Food was scarce, resources were scarce, fertile land was scarce, and so on. So we do have a very hard-wired tendency to be scarcity-oriented. But I think what has happened over time is we don't have to literally fight for our survival every day. I think that as intelligent beings we need to recognize that some of the vestiges of our evolutionary tendencies might be holding us back."

[3.5] When people are made aware of the Horn and Halo effects in ordinary social life, they have little to no qualms concurring that what's being described is anchored by atavistic holdovers which ought to be overcome. It does not seem fantastical to propose the same be done with Horn and Halo effects blurring perspectives in political and economic life. Work in the private sector and the autocrat's hand-picked boss drives you nuts? Democracy at the workplace! Down with the division of labor! Work in a bureaucratic hellhole with all potential competitors prohibited from competing against the tenured nincompoops you're stuck with? Proprietors and legacy wealth to the rescue!

It is only by brushing aside particularity problems and zigzags –– like the competence-to-incompetence spectrum being nonequivalent to the aligned-to-unaligned goals/values spectrum –– that so many are left thinking that the grass is greener.

Unnumbered: With based pills being dropped on the uninitiated so mercilessly –– pills which, for those keeping score at home, can amusingly contradict one another, as seen with the spread of the Black Pill and its not-so-warm reception among Red-Pillers –– I've come to be bothered by the dearth of a Pill Category for thinkers who tout provisionalism and intellectual caution/humility. [Cue the pompous scholarly voice proclaiming well of course, that sounds like an actual respectable position to hold, so why would juvenile anons and basement-dwellers come up with a gimmicky backdrop for something like that?! To which I say, why be dismissive of juvenile anons?! They're increasingly a riot. Plus the whole pill thing has taken on a life of its own, beyond the unholy chan-world of sitting back and watching-it-all-burn-down-nihilistically.] Okay, so now that we all agree that pills aren't hokey, and that finding them hokey makes you totally lame, I hereby nominate the Grey Pill for this title. The Grey Pill is there to remind you not to get too cocky about that buried piece of knowledge you've dug up against overwhelming odds, seeing as all knowledge, including repressed knowledge, has a shelf life. Thus, the Grey Pill is prior to any other colored pill you're fixing to drop on unsuspecting targets.

Follow up to: Nothing But Nostrums

Re. your last video: you're wrong on immigration and race (only watched some of the last parts with Taylor.)

ReplyDeleteI also have a lot in common with my ancestors from 500 years ago, since many of the German tradtions are still part of us, even if only in less urban areas. The reeducation, americanisation and islamisation is doing its best to eradicate it. I can also read Walther von der Vogelweide or Eschenbach, or Luther and Kant and Goethe an feel the Volksseele continuing up into our day.

And given that the non-whites that are forced into our countries are more alien to me than a von der Vogelweide, I do not buy this argument at all.

Let alone that it is inborn to be suspicious of people very different from one's own ethnic background (Eibl-Eibelsfeldt).

It will and already has lowered our mean IQ in Germany -- see Volkmar Weiss' comment that turks lowered PISA results -- and it will also lower trust.

High trust societies as we have in the West are not the norm. The Church has most likely played a role due to the ban on cousin marriages; there is less incest and nepotism in Western countries.

Lastly, immigration is war and vice versa. Vox Day's first "Voxiversity" "Immigration & War" is dedicated to exactly this (refering to an essay by leading military historian Martin van Creveld called "Migration and War").

Midwit,

DeleteWhy comment here and not on the video? This post has nothing to do with any of the topics I raise in my video. If you want halfway speedy replies from me, you're likelier to get them by commenting on my videos. I rarely check blogger.

You say I'm wrong on immigration and race, but you don't (1) describe what my specific prescriptions for immigration in America even are, and (2) don't spell out your specific prescriptions for immigration and why they're wiser.

In the video, I stressed the importance of being open to arguments accounting for "everything in between" the minimum and maximum rates of influx; rates which would vary country by country, as determined by majoritarian will, not by congress or any other top-down scheme. Why would you tell someone they're wrong on immigration when they're incredibly flexible on it? If anything, you should have said "you're not entirely right" and gone on to explain why the "majoritarian will" approach is only part of the story, or something.

"I also have a lot in common with my ancestors from 500 years ago"

I'm sure you do. I probably do as well. But if I single out one common practice by the in-group from 500 years ago that's no longer common today (say, inbreeding) among the various out-groups living within your region or near your region, and ask you to accept a package-deal pertaining to your in-group from 500 years ago versus a package-deal pertaining to those out-groups today, I doubt you'd sincerely pick the in-group. Only by omitting or downplaying the now glossed-over practices common 500 years ago (inbreeding, or insert-medieval-norm-here) will you come away believing that the aesthetic similarities you're so hung up on are enough of a conjoiner between you and your ancestors to compensate for all the ideological and attitudinal dissimilarities.

I could be mistaken, of course, in that you're nowhere near as mortified by inbreeding and general medievalism as the average modern German is. If so, you'd be an outlier, which poses no issues for my original point: for the general population, temporal dissimilarities are almost always more weighty than genetic ones.

For most people, most of the time, assimilation along in-group/out-group lines, though certainly a tall task (contrary to what xenophiles what to tell themselves), is still a much less daunting task compared to having to assimilate to a world ruled by notions of The Divine Right Of Kings, theocracy, nobility, servility, righteous disposability, illiteracy, intellectual unfreedom, etc. Give me my least favourite immigration policy before you give me that. Just about anything before that.

Don't fall for: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Romantic_nationalism

As for race, I can't be "wrong on race" when I have incomplete and non-committal views on race. If that's enough to be wrong, the implications are that everyone should have strong views on race, because the jury is in. But the epistemic jury is hardly in. Much of what was "in" 30 years ago is "out" now, and I don't see why the same won't hold for the next 30 years, and so on. (1/2)

(2/2)

DeleteFrankly, you sound like someone who's totally sold on genetic determinism and racial essentialism. In my experience, people who want to believe this generally don't budge. I've seen people whose job partially or entirely rests on them having thoroughgoing knowledge of genetics and biology fail to dissuade the essentialists to even a modest degree, so I get the sense that I'm ill-suited for the task. But for what it's worth, here's one (of many) summations going over why this is by no means a settled matter: http://www.councilforresponsiblegenetics.org/ViewPage.aspx?pageId=73

Snippet from the article: "The heritability of g appears to rise to about .75 (75%) by late adolescence. One explanation for this shift is that family influences on cognition are deemed to diminish throughout development. Also possible, explains Plomin, is that additional gene expression delayed during childhood may be triggered as cognitive processes develop.

But do these studies provide evidence that intelligence is inherited? Causation has not been determined here. There are two significant problems associated with twin/adoption and family studies. First is the assumption that genetic effects can be separated from environmental effects. This position rests on the “equal environments assumption” (EEA), which posits that the environment of individuals in the same or different homes can be controlled for in such a way that genetic effects can be separated out. There have been serious critiques levied at EEA due to the way adoptive and non-adoptive environments are appraised as being different or alike [19]. Additionally, the idea that genetic and environmental effects are simply additive and work in isolation of one another is false.

Second, a majority of these studies do not account for how IQ outcomes are affected by class differences. Eric Turkheimer, et al. utilized the twin/adoption and family method to show that socioeconomic status modifies heritability of IQ in young children [20]. The study found that in families who subsisted on incomes at or below the poverty line, the heritabilty effects on IQ were close to zero, whereas in affluent families, these effects were quite high. They also found that parental education levels modified both the effects of heritability and environment, increasing the former and decreasing the latter as years of education increased. In cases where adequate nutrition, access to education, protection from exposure to environmental toxins, and similar issues have affected the development of individuals, heritability estimates have been shown to be expressed quite differently.

Another phenomenon that seems to refute current heritability estimates is the “Flynn effect [21],” which describes a steady worldwide rise in performance since testing began. A three-point rise in IQ per decade on average has been noted, even when tests have been re-standardized to account for these gains. The reasons for this rise are not known, but one explanation involves children’s need, and the need of people in general, to adapt to the increasing complexity of modern life. Obviously the rise cannot result from genetic mutation as the time frame is too narrow. Rather, the Flynn effect may demonstrate how flexible human cognitive development really is. As successive generations take in greater, and more complex, amounts of information from shifting sources such as television and radio, they learn to process the increase. The phenomenon calls into question the extent to which g is an inborn trait. Members of the American Psychological Association task force underscored in their 1995 report that: “…heritable traits can depend on learning and they may be subject to other environmental effects as well. The value of heritability can change if the distribution of environments (or genes) in the population is substantially altered [22].”"

The author sources to dozens of references at the bottom, in case you're dissatisfied with the article itself.

Addendum: apart from the fact that Germans 500 years ago looked very similar to Germans today. See also Andreas Vonderach "Gab es Germanen?".

ReplyDeleteAnd the argument Zakaria brought up with the mingling between Angles and Normans etc. is misleading, since they were not just of the same race, but also of the same . To quotsubracee from John Baker's "Race" (from archive.org, formatting might be messy):

It has been stated that the English were ‘a truly multiracial society’ because

there were Angles, Saxons, Jutes, Normans, Belgics, and ‘flamboyant Celts’

among their ancestors.! 11 79] The reader should note that all these peoples were

not only of one race (Europid) but of one subrace (Nordid). Incidentally it is

doubtful whether the Angles and Saxons were different peoples in any

sense.! 10! ]

It follows from what has been said that the English are far from being ‘one of

the most mongrel strains of the human race". The facts can perhaps be best

represented by use of a rough analogy. Let us suppose that a dog-breeder has

been specializing in harriers (hounds for hare-hunting, an ancient breed). Let us

suppose further that it occurs to him to mate some of his harriers with

bloodhounds. He keeps his stock of harriers and makes a new hybrid breed of

bloodhound-harriers. He gives some of each stock to a master of foxhounds.

The master incorporates them in the breeding stock of his pack, and later in¬

troduces some otterhounds as well. Interbreeding for several generations even¬

tually produces a varied but roughly homogeneous pack, all the ancestors of

which were hounds of the long-eared group that hunts by scent.

No one, on seeing the pack, would say that these hounds were one of the

most mongrel of all the strains of dogs. The man-in-the-street would simply say

that they looked rather like foxhounds, while a huntsman would remark on the

differences from typical members of the breed. The inexpert and the expert

would agree, rightly, in describing a cross between a bull-dog and a greyhound,

or between a Pekinese and a beagle, as a genuine specimen of one of the most

mongrel of all the strains. Comparable examples could be quoted from

mankind, but since the word ‘mongrel’ is disparaging when applied to man, it is

far better to avoid it.

In the analogy just related, the Neolithic (Mediterranid) people are

represented by the harriers; the Beaker Folk by the bloodhounds; the Iron Age

invaders (Celtae and Belgae) by the foxhounds; and the Anglo-Saxons and

other northerners by the otterhounds. Only the Beaker Folk were markedly

different from the rest (though of the same race), just as the bloodhounds were

among the dogs (though of the same group of breeds).

The people of a large part of Wales would be represented, in an analogy of

268

SELECTED HUMAN GROUPS

this sort, by a pack of foxhounds to which the breeder of harriers had made a

much bigger contribution of his unhybridized stock to the master of foxhounds

than he did in the case just considered.

It is a remarkable fact that those in the British Isles who spoke a language

derived from the dialects of the Iron Age invaders forgot the origin of their

speech. They did not realize that it had been handed down to them from the

people whom Caesar had called Celtae and Belgae, and for more than a millen¬

nium and a half it did not occur to anyone to call the language (in its various

forms) 'Celtic’, or the people who spoke it ‘Celts’. It was a strange Scottish

Latinist and humanist, George Buchanan (1506-82), at one time a prisoner of

the Spanish Inquisition, who first revealed the facts. By studies of the classical

authors, but especially of place-names, he reached the conclusion that the

‘GallV or people of central France in ancient times must have spoken a

language similar to that used in his own country by particular groups of people.

The salient passage in a long and detailed argument is this:

lam tande eo ventu est, ut ex oppidorum, fluminu, regionu, & alijs id genus

[…]