The end of 2017 is fast approaching and I've only managed to offer up one (deadly long) post all year. A downer. On ambitious days, the goal was to have an uneven five presentable by year's end. As is often the case, whatever time I devoted to improving dusty drafts only saw them deteriorate by becoming overwritten and inconsumable. Not unintelligible, just inconsumable, and only so for the external reader who isn't magically cohabiting my headspace. How dare they, those non-me people.

In truth, I'm being half-serious here, having reached the point where one persistently intrusive element of my psyche feels justified in scorning readers for not living in my head so as to absorb my content better. Thankfully, all the other parts of my psyche are still sane enough to know better. For now.

Anyway, I don't see any of those unfinished posts getting completed in the coming days/weeks, so rather than have myself attempt a hasty job on a random isolated topic, I'll try to pull off a hasty job on a general rundown of topics which I continue to be preoccupied with daily.

Call it a "Doxastic Clip Show" post.

Axiological takeaway:

· Lexical Welfarism >

The Rest

· The Good Is Always Prior To The

Right

The usual way around this involves contending/pretending that there isn't enough reachable torment near/at/above the designated (read: unspeakably bad) threshold level. If you buy that, the perpetuation of all such horrors, though regrettable, is believed to fall short of any mandate that would have us subordinate all non-welfarist priorities to the vulgarly welfarist ones which are in overabundance. That is, it doesn't warrant situating 'rightness' as posterior to 'goodness' in all cases, just in some cases. I disagree and maintain that there is enough torment –– more than enough –– and that it remains reachable, reducible, and overridingly important at this juncture.

Tragedy at this scale is ever-present and open to inexhaustible amounts of alleviation, especially for the technologically inclined. Grant this much and no pluralistic contrivance hinders it, insofar as the general state of affairs continues to be as irredeemably bad as it has steadily been. Rid Omelas of its one torture victim, then talk to me about your sophisticated and highly nuanced value-set (i.e. "Welfarism<The Rest" or "Welfarism=The Rest").

Some

implications:

· Value Monism > Value Pluralism

· Preventing Disvalue > Creating Value

· Decreasing Extant Disvalue > Increasing Extant Value

Theories of wellbeing:

· Preferentism (for autonomous humans)

· Hedonism (for non-human beings and

non-autonomous humans)

· Objective List Theories (for no one) [oh

snap]

The update? My beloved preferentism runs into considerable obstacles, some of which may prove fatal

regardless of whether defenders recommend a raw

or ideal form of it, or some combination thereof. Holding out hope for some epic hybrid of the standalones is like betting on the wildest of wildcards, at this point. It's clear to me that the mere prospect of a knockdown incarnation of preferentism –– where its best offering stands impenetrable against all biting criticisms from hedonists –– is a philosophical fantasy.

One big

problem preferentists face that hedonists easily avoid is that ordinary preferences tend to be temporally-delicate. When goals and fears are irreversible, their irreversibility opens us up to the realization of permanent value/disvalue, which quashes the otherwise transient mode of value/disvalue. When a preference is formed and frustrated, it remains so unless it is consciously overturned by the preferring subject. For a good example, take the prudential value of contextual and/or local anti-mortalism as a given. Premature death is said to

be Infinitely Bad for the subject who dies while his desire to remain alive is firmly in tact. This makes the badness of death intransient and, I can only assume, evaluatively incommensurable in some principled sense.

How do you even start thinking about a trade-off with unique costs/benefits when one of the quantities at hand is billed as being infinitely good/bad? You can't. Well, I suppose you can, but doing so involves negating all finite harms (i.e. extreme suffering that doesn't kill the sufferer) so as to cater to the prevention of all infinite harms (i.e. painless involuntary deaths). But even here, the aggregative preferentist would be swimming against a perpetual tide, seeing as it takes but one reluctant death –– premature or not –– to tip the disvalue scale into perpetuity. We could say the same for pro-mortalists who rejoice at the prospect of their own death; grant their wish and see the everlasting benefit –– accrued to them postmortem –– instantly realized and locked-in. In both cases, any additive talk of good/bad turns incoherent. For additive commensurability to pass the coherence bar, the metaphysical imprint of value/disvalue must be finite and localized. This holds doubly if one cares to apply standard cardinal arithmetic to value/disvalue throughout the bargaining process, presumably in acknowledgement of the unavoidable implications of cost vs. benefit analysis.

How do you even start thinking about a trade-off with unique costs/benefits when one of the quantities at hand is billed as being infinitely good/bad? You can't. Well, I suppose you can, but doing so involves negating all finite harms (i.e. extreme suffering that doesn't kill the sufferer) so as to cater to the prevention of all infinite harms (i.e. painless involuntary deaths). But even here, the aggregative preferentist would be swimming against a perpetual tide, seeing as it takes but one reluctant death –– premature or not –– to tip the disvalue scale into perpetuity. We could say the same for pro-mortalists who rejoice at the prospect of their own death; grant their wish and see the everlasting benefit –– accrued to them postmortem –– instantly realized and locked-in. In both cases, any additive talk of good/bad turns incoherent. For additive commensurability to pass the coherence bar, the metaphysical imprint of value/disvalue must be finite and localized. This holds doubly if one cares to apply standard cardinal arithmetic to value/disvalue throughout the bargaining process, presumably in acknowledgement of the unavoidable implications of cost vs. benefit analysis.

Luckily for hedonists,

neurologically tracked experiences [mental states] are by their creaturely nature impermanent and fleeting.

At least from subject to subject, and barring any theological babble of a neverending afterlife for each subject. Assuming this remains uncontroversial, value/disvalue is always transient

and never permanent under all hedonic theories of wellbeing. This is certainly more Neat And Tidy compared to the inelegant

complications posed by eternally-binding desires and aversions within non-hedonic/anti-hedonic theories.

Despite all this, preferentism is the least vexatious option for the autonomous sectors of humanity, given the usual issues of meddlesomeness a rival theory like hedonism is bound to bring. I've complained about those indefatigably in the past and I'm sorry to say that I still can't seem to let them slide, try as I might. Nor am I willing to decouple prescriptive force from axiological wisdom, as some are quick to do when they reach the same/similar impasse. This is why I grudgingly scrapped the book I had planned on writing last year. It came down to my reckoning with our inability to resolve or dissolve the shortcomings of preferentism. Had I thought those gaffes to be of minor importance, I would've been willing to proceed without caution. Sadly, the "permanent vs. transient" value/disvalue complication is little more than a trite quarrel. It's a big fucking deal, and coming to terms with it is no joyride. The whole ordeal has me in a state of semi-paralysis.

None of this is to imply that I am prescriptively paralyzed. Far from it. Lasting complexities for autonomous beings will never shortchange the clear-cut simplicities regarding how we should treat non-autonomous sentient beings; they should be treated with hedonic gloves and nothing but. I would extend the same for autonomous beings whose preferences clash on an interpersonal level; whenever a qualitatively-traceable aversion conflicts with a non-qualitative one, I'll recommend tending to the qualitative aversion when said aversion is near/at/above the lexical [non-cumulative] set-point.

[Update 2017-12-30: I should specify that my uses of 'cumulative' or 'summative' are meant to signal disharmony with lexical welfarism, whereas my uses of 'additive' or 'aggregative' can still be applied to lexical welfarism, seeing as value lexicality does not stand in the way of aggregating all things at/near/above the designated set-point. Its main gripe is with holism].

None of this is to imply that I am prescriptively paralyzed. Far from it. Lasting complexities for autonomous beings will never shortchange the clear-cut simplicities regarding how we should treat non-autonomous sentient beings; they should be treated with hedonic gloves and nothing but. I would extend the same for autonomous beings whose preferences clash on an interpersonal level; whenever a qualitatively-traceable aversion conflicts with a non-qualitative one, I'll recommend tending to the qualitative aversion when said aversion is near/at/above the lexical [non-cumulative] set-point.

[Update 2017-12-30: I should specify that my uses of 'cumulative' or 'summative' are meant to signal disharmony with lexical welfarism, whereas my uses of 'additive' or 'aggregative' can still be applied to lexical welfarism, seeing as value lexicality does not stand in the way of aggregating all things at/near/above the designated set-point. Its main gripe is with holism].

As for Objective List Theories, I see them as a smokescreen for conventionalism and

extroversion. Maybe there are some clever exceptions to the rule, but I am yet to come across any. Ditto for the borg-affirming theory of perfectionism and its many mutations. None of these conceptions of the good have "the stuff" if you're at all skeptical of Mother Nature.

-------- -----

Population

Axiology:

· Person-affecting views ala Actualism

· Person-affecting views ala Variabilism

Still exploring

the sinuous distinctions between these two.

Zero Tolerance

For:

·

The

Repugnant Conclusion

·

The

Sadistic Conclusion

·

Mere

Addition Principle

·

Any

of the other "more is better" takes

Prescriptive takeaway:

All moral

theories are flawed and imperfect, but that's hardly a novel observation for those paying close attention. This is how I rank the imperfections and fumbles from best to

worst:

·

Consequentialism

> Deontology > Virtue Ethics >

Proportionalism > Contractarianism > Natural Law Theories > Divine Command Theories

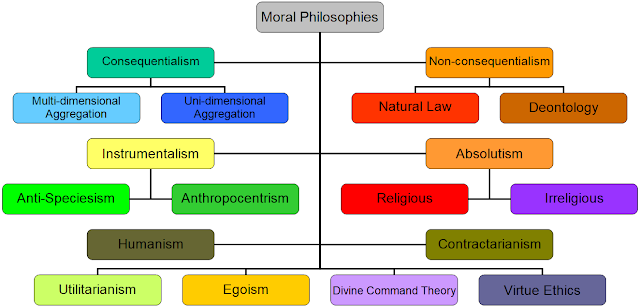

Here's a little sketch that includes a few other components of moral theories... while excluding proportionalism... because I ran out of space:

Haidt coined "Moral Elevation" as a homage of sorts to Thomas Jefferson who "had described the emotion in detail in a letter discussing the benefits of reading great literature". Okay. If expecting analytic moral philosophy to circumvent such mawkishness is asking too much, then I'm left wondering what if anything sets the analytical facet of moral philosophy apart from commonsensical folk morality. If there was ever a line to be brazenly drawn somewhere, it is here.

The line is guaranteed to not sit well with any ethicist who holds that the world is and has always been good enough for a multiplicity of agendas to stay on The Radar, for The Radar must contain a modicum of balance. Not sure if this crowd is any more swayable today as compared to every other point in history. The historical record speaks volumes on what balance has done for my agenda here. If you see yourself as a suffering-minded student of moral philosophy, but also claim that their balanced bestrew plays a non-derivative role in what well-adjusted fortunate agents ought to care about, then you've been taken for a ride by espousers of pluralism. Authors who, in the best case, deceive themselves into thinking they are mortal enemies of unfathomable misery. And in the worst case, by authors who pay lip-service to the primacy of stamping out all such misery, and that the right kind of pluralism can fit in with the sheer urgency of your oppositional project.

Consider how the aforementioned "moral" elevation –– alongside warm fuzzies altogether –– serves as the flipside of the "moral disgust"

phenomenon. Disgust-driven morality is well-documented, but the academic defenders of ethical pluralism that I've read don't have any of that in mind when insisting on a balanced set of priorities. I just go one step further; shunning beauty-driven morality all the same. You might think there's some asymmetry between the moralization of disgust vs. beauty, but I disagree. Just as suffering-reducers have to put up with neuro-types who are quick to ascribe condemnatory proscriptive force to mundane things that repel them psychologically (i.e.

homosexuality, bisexuality, "degeneracy", clemency, disloyalty per se, dark humor, etc.), suffering-reducers concomitantly put up with certain other neuro-types ascribing prescriptive force to random things that delight

them psychologically. Fanciful things like beauty and poetry and diversity and solidarity and friendship and "love". On both fronts, the harm-reducer seems justified in asking "How much blood

ought to be spilled in the name of your anti-disgust and/or elevation?". The

answer, if it is at all honest, will without exception be "some". Some blood, for without the spillage, it is impossible perpetuate purities and elevations, just as it has always been impossible in the past. Incommensurable pluralism demands it. A proper consequentialism irreverently shuts it down before it gets a foot in the door.

Do all variants of consequentialism succeed at shutting it down? Absolutely not.

Recommendable

variants include:

·

Negative

Consequentialism (or just negative-leaning)

Stonewalling positive consequentialisms follows from my rejection

of all non-negative positions in Population Axiology. Go figure. And so, consequentialists who wish to mount a case for a clean transferability between positives and negatives must first explain why person-affecting views (actualism or variabilism) carry more baggage compared to the world-affecting "more is better" spins. I predict they'll fail at this, because it's the other way around.

To drive the point home, I think I'll start referring to all "positive" consequentialisms as

"suffering-downplaying" consequentialisms.

Next up:

·

Scalar

Consequentialism > Deontic Consequentialism

This is to underscore

that 21st Century moral thought should not task thinkers with figuring out how to live

"The Good Life" and is best thought of as a conceptual tool for

ranking states of affairs per the summed individual interests of sentient beings. This is meant to neutralize duty-themed attempts at figuring out whether the agent is supposed to maximize or satisfice the good. With this neutralized, the truly hard work stems from actual vs. potential vs. counterfactual assessments of betterness and worseness. Due to this narrowing, intra-consequentialist talk will prove a far cry from the storied "obligatory vs. supererogatory vs.

forbidden" treatments of act-types. Frankly, there should never have been such a thing as deontic consequentialism. Many objections levied by non-consequentialists actually start to sound compelling when you misuse the theory this way.

We can happily

acknowledge that scalar alternatives leave much to be desired when it comes

to (1) determining the deontic status of many or most acts, (2) determining the aretaic status of moral agents, (3) providing satisfactory

answers to numinous questions like "What's in a man's

heart?" or similarly essentialist spins on the function of ethics. Non-evaluative riddles of this sort are purely derivative; no different from run-of-the-mill questions concerning moral know-how.

Messages over messengers, as I always say. The quicker we relinquish all-things-deontic/aretaic to the ash heaps of history, the better.

Next:

·

Dual

Consequentialism > Plain Consequentialism

Since so many aspects of modern life are hopelessly unpredictable, even to the highly deliberative and

cautious moral agent, the decisional status of moral pseudo-properties like

"rightness" or "wrongness" will often be ambiguous. This registers with plain consequentialists in some ways, but in many other ways it fails to. Plain consequentialists are stuck with outmoded notions of decent and indecent people, just as non-consequentialists have always been. To be sure, I know this feeling. My psyche still succumbs to it all the time. I will probably never stop feeling like there are good and bad people in the world, that these notions I carry around of good/bad folk are justifiably invariant, and that their centralized core selves are something other than voidable. But what I feel day-to-day isn't necessarily so. People are just their brains, and the circuitry is unchosen.

I don't need to tell anyone that such feelings have only been amplified thanks to internet-induced sectarianism. Once someone makes a bad impression on us online –– in light of an intellectually dishonest or straight-up reprehensible view they've voiced –– that impression is there for keeps. If the bad impression originates from what they advocated for, odds are we will hold the advocate in contempt until the bitter end. After all, people who are outspoken rarely go on to disavow the views they spouted off in public. It's just not how all of this works. And so, the judgers have no real reason to disavow their negative judgments (of the speaker's character or identity). Now for the buzz-kill: concepts like "character" and "identity" are far more malleable and dissolvable than we like to think (that is; than we evolved to perceive).

The stretchiness of it all becomes even more pronounced when you place a moral premium on the agent's attentiveness to decision-procedures for optimal outcomes. This amounts to a moral dream. Even if you reason flawlessly about the foreseeable nearsighted [direct] consequences of your next act, you as a fallible brain can never reason flawlessly to connect enough dots pertaining to the farsighted [indirect] consequences of said act. This leaves "plain" telic verdicts in something of a pickle. Oh sure, blame and praise will be doled out based on what is plainly reasoned to be an expected outcome rather than unexpected one, but that's only as useful as the effects are agentially connectible and local.

To make matters worse, consequentialists never really pin down the point at which direct consequences morph into so-called indirect consequences. We just declare a fine line between direct/indirect effects and internalize our declarations as unambiguous. But the line is pretty damn illusive if you stop to think about the minutia of it all. In contemporary western society, most consequences are ricochets and unforeseeable. Unless we retrieve back to small-scale communal living, this won't change anytime soon. If anything, the unforeseen carryover effects of human behavior are bound to get more scattered and unpredictable.

Think of it this way; maybe some mastermind out there does possess the faculties needed to reason proficiently about the far-future (i.e. centuries or millennia) and to put that reasoning to good use. Even so, there is something absurd in pointing to an amoral talent as a tiebreaker that boosts his moral performance above the moral performances of people who sacrifice as much as he does, but who through no fault of their own get stuck with reasoning skills that max out at the comparative near-term (i.e. months or years or decades) only.

Point being, our inability to reason over far-reaching impacts is only a problem for Plain Consequentialists who are under the impression that there is no ambiguity when it comes to reasoning behind "right vs. wrong" acts, and that a substantive moral theory has the burden of being agent-situated rather than (only) patient-situated. Well, I've always taken my deliberating to be a patient-centered project. It's not supposed to be something that reflects well on me in light of my thinking about it, or even in light of my trying to do something about it after thinking about it. The rest ("The Rest") was window dressing To date, no persuasive argument to the contrary has crossed my path.

A "Dual" alternative helps to dissolve many of the endemic problems one runs into when asked by non-consequentialists "Just how virtuous is agent so-and-so compared to agent so-and-so, on your view?". The answer is often a non-answer: A rapist who prevents 999 rapes for every 1 rape they commit isn't "morally superior" to the apathetic non-rapist who nets zero impact over a lifetime. That much is clear. But things turn dicey when you try to compare the virtuousness vs. viciousness of the preventive 999/1 'ratio-rapist' to the virtuousness vs. viciousness of a would-be rapist who frets too much about the possibility of getting caught to ever go through with it. Those frets aside, the would-be rapist would readily go through with it. Can any type of consequentialism provide a clear-cut answer on who is superior/inferior here? An answer that "goes beyond" patient-centered evaluations and accommodates agent-centered ones? Nope. Is that a strike against it? Nope. But you have to ask: Can any other moral theory pull the rabbit out from under this hat? Not really. Not unless you make it a point to romanticize the function of morality at the outset. Non-consequentialists do this in droves by (1) insisting that the deontic is prior to the evaluative, and (2) positing this discernable thing called "personal identity" as something that is in principle comparable from subject to subject.

Believing babyish things like "John Smith didn't have a vicious bone in his body, the man was a sweetheart from cradle to grave!" is as much, if not more, of an epistemic crapshoot as the "You can't measure and/or aggregate qualia!" pseudo-checkmate is. You know, the supposedly non-epistemic checkmate welfarists still have to hear about. I recognize that qualia is intangible and that calculating it is beyond our reach at this time. It will probably always be that way. But the same can be said of John's nearest and dearest; people who didn't know a damn thing about John's innermost supressed proclivities. Oftentimes, John Smith will himself not be consciously aware of such proclivities throughout his life. The human brain's capacity for self-deception and self-schema upkeep appears to have little in the way of limits. Dark recesses, reputational self-management, the ways of the subconscious, crude urges blocked out and relegated to the unnoticed level, et cetera.

I'm not convinced that a widening of the moral bull's-eye gets you anywhere on this. It just duplicates the longstanding (epistemic?) problems each standalone theory is saddled with, whether that has to do with reading minds from cradle-to-grave in order to assess agents' virtue/vice statuses over a lifespan, or whether it has to do with measuring and comparing everyone's qualitative experiences over the course of all space and time. Both sets of mental 'data' may prove impossible to discover and compare, no matter how refined our empirical tools get. Thus, any remedy that urges enlarging and/or combining different moral theories misses the point entirely. How is pluralistic compromise any different here from the more daft pluralistic compromises, like letting "symbolic value" edge out impact in some circumstances?

I don't need to tell anyone that such feelings have only been amplified thanks to internet-induced sectarianism. Once someone makes a bad impression on us online –– in light of an intellectually dishonest or straight-up reprehensible view they've voiced –– that impression is there for keeps. If the bad impression originates from what they advocated for, odds are we will hold the advocate in contempt until the bitter end. After all, people who are outspoken rarely go on to disavow the views they spouted off in public. It's just not how all of this works. And so, the judgers have no real reason to disavow their negative judgments (of the speaker's character or identity). Now for the buzz-kill: concepts like "character" and "identity" are far more malleable and dissolvable than we like to think (that is; than we evolved to perceive).

The stretchiness of it all becomes even more pronounced when you place a moral premium on the agent's attentiveness to decision-procedures for optimal outcomes. This amounts to a moral dream. Even if you reason flawlessly about the foreseeable nearsighted [direct] consequences of your next act, you as a fallible brain can never reason flawlessly to connect enough dots pertaining to the farsighted [indirect] consequences of said act. This leaves "plain" telic verdicts in something of a pickle. Oh sure, blame and praise will be doled out based on what is plainly reasoned to be an expected outcome rather than unexpected one, but that's only as useful as the effects are agentially connectible and local.

To make matters worse, consequentialists never really pin down the point at which direct consequences morph into so-called indirect consequences. We just declare a fine line between direct/indirect effects and internalize our declarations as unambiguous. But the line is pretty damn illusive if you stop to think about the minutia of it all. In contemporary western society, most consequences are ricochets and unforeseeable. Unless we retrieve back to small-scale communal living, this won't change anytime soon. If anything, the unforeseen carryover effects of human behavior are bound to get more scattered and unpredictable.

Think of it this way; maybe some mastermind out there does possess the faculties needed to reason proficiently about the far-future (i.e. centuries or millennia) and to put that reasoning to good use. Even so, there is something absurd in pointing to an amoral talent as a tiebreaker that boosts his moral performance above the moral performances of people who sacrifice as much as he does, but who through no fault of their own get stuck with reasoning skills that max out at the comparative near-term (i.e. months or years or decades) only.

Point being, our inability to reason over far-reaching impacts is only a problem for Plain Consequentialists who are under the impression that there is no ambiguity when it comes to reasoning behind "right vs. wrong" acts, and that a substantive moral theory has the burden of being agent-situated rather than (only) patient-situated. Well, I've always taken my deliberating to be a patient-centered project. It's not supposed to be something that reflects well on me in light of my thinking about it, or even in light of my trying to do something about it after thinking about it. The rest ("The Rest") was window dressing To date, no persuasive argument to the contrary has crossed my path.

A "Dual" alternative helps to dissolve many of the endemic problems one runs into when asked by non-consequentialists "Just how virtuous is agent so-and-so compared to agent so-and-so, on your view?". The answer is often a non-answer: A rapist who prevents 999 rapes for every 1 rape they commit isn't "morally superior" to the apathetic non-rapist who nets zero impact over a lifetime. That much is clear. But things turn dicey when you try to compare the virtuousness vs. viciousness of the preventive 999/1 'ratio-rapist' to the virtuousness vs. viciousness of a would-be rapist who frets too much about the possibility of getting caught to ever go through with it. Those frets aside, the would-be rapist would readily go through with it. Can any type of consequentialism provide a clear-cut answer on who is superior/inferior here? An answer that "goes beyond" patient-centered evaluations and accommodates agent-centered ones? Nope. Is that a strike against it? Nope. But you have to ask: Can any other moral theory pull the rabbit out from under this hat? Not really. Not unless you make it a point to romanticize the function of morality at the outset. Non-consequentialists do this in droves by (1) insisting that the deontic is prior to the evaluative, and (2) positing this discernable thing called "personal identity" as something that is in principle comparable from subject to subject.

Believing babyish things like "John Smith didn't have a vicious bone in his body, the man was a sweetheart from cradle to grave!" is as much, if not more, of an epistemic crapshoot as the "You can't measure and/or aggregate qualia!" pseudo-checkmate is. You know, the supposedly non-epistemic checkmate welfarists still have to hear about. I recognize that qualia is intangible and that calculating it is beyond our reach at this time. It will probably always be that way. But the same can be said of John's nearest and dearest; people who didn't know a damn thing about John's innermost supressed proclivities. Oftentimes, John Smith will himself not be consciously aware of such proclivities throughout his life. The human brain's capacity for self-deception and self-schema upkeep appears to have little in the way of limits. Dark recesses, reputational self-management, the ways of the subconscious, crude urges blocked out and relegated to the unnoticed level, et cetera.

I'm not convinced that a widening of the moral bull's-eye gets you anywhere on this. It just duplicates the longstanding (epistemic?) problems each standalone theory is saddled with, whether that has to do with reading minds from cradle-to-grave in order to assess agents' virtue/vice statuses over a lifespan, or whether it has to do with measuring and comparing everyone's qualitative experiences over the course of all space and time. Both sets of mental 'data' may prove impossible to discover and compare, no matter how refined our empirical tools get. Thus, any remedy that urges enlarging and/or combining different moral theories misses the point entirely. How is pluralistic compromise any different here from the more daft pluralistic compromises, like letting "symbolic value" edge out impact in some circumstances?

Next:

·

Multi-dimensional

Consequentialism > Unidimensional Consequentialism

In other words:

·

Aggregative

Particularism > Aggregative Principlism/Generalism

My "Moral Particularism" circa 2014/2015 was nothing of the sort. I've always been a Moral Generalist and/or Principlist. What I wasn't, and what I am still not, is an aggregative generalist/principlist. Though I believe there is an overriding master imperative, I don't think we get there by aggregating welfare along strictly utilitarian or strictly prioritarian or strictly egalitarian lines, as unidimensional consequentialists would have it. Enter multidimensional spin-offs, like the flagrant variability between total and average utilitarianism based on a population size that is in a state of flux. Assuming the only options to choose from are utilitarian ones, a smaller population would do well to cater to total utility while it is small, whereas larger populations would be wise to use average utility in determining how things are going. Totalism can be a disaster for large clusters of moral patients, just as Averagism can be for the small clusters. This holds regardless of whether your broader moral agenda is to increase extant value or to decrease extant disvalue.

Aggregation is always context-dependent and numerally fragile. Look at it the way you would look at a game of chess: The more room you have, the more moves you can make, the lower your likelihood of getting checkmated becomes. Options don't make you "unprincipled". They make for a winning strategy. So it is with aggregative ethics. Openness to total/average/other variability helps shield aggregation from otherwise debilitating criticisms.

All well and good, but the grand prescription falls unapologetically within the walls of generalism. An actual moral particularist would contend that aggregation itself ought to be sent packing in many cases, as forward-looking reasons don't capture the entirety of moral reasoning. I'd obviously disagree, but there you go.

Aggregation is always context-dependent and numerally fragile. Look at it the way you would look at a game of chess: The more room you have, the more moves you can make, the lower your likelihood of getting checkmated becomes. Options don't make you "unprincipled". They make for a winning strategy. So it is with aggregative ethics. Openness to total/average/other variability helps shield aggregation from otherwise debilitating criticisms.

All well and good, but the grand prescription falls unapologetically within the walls of generalism. An actual moral particularist would contend that aggregation itself ought to be sent packing in many cases, as forward-looking reasons don't capture the entirety of moral reasoning. I'd obviously disagree, but there you go.

Agential considerations for evaluative overviews:

·

Agent-neutral

theories > Agent-relative theories

· Impartialism > Altruism & Egoism

[Self-inclusive

> Self-disregarding & Self-absorbed]

Agential considerations for practical [non-evaluative] decision-making on the ground:

Agential considerations for practical [non-evaluative] decision-making on the ground:

· Contextualism > Agent-neutrality >

Agent-relativity

Metaethics:

I don't know.

Uncertainty here is more of a big deal than I'd like to admit, but I just don't know.

Uncertainty here is more of a big deal than I'd like to admit, but I just don't know.

My metaethical

past is shaky and includes, in this particular order:

Robust realism,

anti-realism, constructivism, robust realism (again), quasi-realism, and

probably some other in-between view that I'm now omitting, like "deflationary realism" or fictionalism.

And that's not

even broaching the cognitivism vs. non-cognitivism divide, or

the naturalism vs. non-naturalism divide.

All I know at this point is that I'm okay with a staunch commitment to Moral Fallibilism, which is saying very little.

Also, the SEP has

a fine entry on "Moral Skepticism" and a particularly stellar subsection on non-dogmatic versions of it. This can be found by keyword searching "Pyrrhonian Moral Skepticism". I can get on board with that, which means I lean closer to weak irrealism than I do to weak realism.

A peculiar add-on, in the event that moral facts are as imagined as astrological facts have always been, is how this strangely compliments philosophical pessimism. Just consider how much worse the world we live in is when asserting the existence of moral truths is like asserting the existence of any old woo. I view it as a meta-tragedy; when all celebrated heroes are nothing but the collective projections of those who cheered them on. When we cannot demonstrate to giddy torturers who torture for their own base amusement that they are less in touch with one (just one!) aspect of reality for doing so. When we, in the name of intellectual honesty, must resort to pleading with vile sadists on unanalytical emotive grounds, on the odd chance that they finally start coming around to our way of seeing things. All of it is, at the very least, dignity-cancelling; pleading with monsters. I don't want to do it. I want to tell them that they are deluded, in some way. But I don't think my explications have the legs to withstand a meta-marathon this exhaustive.

If you think that swimming in shit is bad enough when moral facts exist, believe me when I say that their absence makes the shit radioactive. It also opens the door to rampant propaganda and deceit, mainly for those who continue to regard victory over the monstrous as having top priority. If you're still reading this, your opponents are probably diehard triumphalists. Regardless of their metaethical views, triumphalists will always talk as if the reality of mind-independent morality is there for all to grapple with. If you retort with "No, it's actually not, but hear me out anyway because we can still construct our ethics, just how existentialists taught us that we can fabricate our own meaning!" the demagogues and their lackeys will make short work of you.

Hell, I will make short work of you.

Supererogation:

A peculiar add-on, in the event that moral facts are as imagined as astrological facts have always been, is how this strangely compliments philosophical pessimism. Just consider how much worse the world we live in is when asserting the existence of moral truths is like asserting the existence of any old woo. I view it as a meta-tragedy; when all celebrated heroes are nothing but the collective projections of those who cheered them on. When we cannot demonstrate to giddy torturers who torture for their own base amusement that they are less in touch with one (just one!) aspect of reality for doing so. When we, in the name of intellectual honesty, must resort to pleading with vile sadists on unanalytical emotive grounds, on the odd chance that they finally start coming around to our way of seeing things. All of it is, at the very least, dignity-cancelling; pleading with monsters. I don't want to do it. I want to tell them that they are deluded, in some way. But I don't think my explications have the legs to withstand a meta-marathon this exhaustive.

If you think that swimming in shit is bad enough when moral facts exist, believe me when I say that their absence makes the shit radioactive. It also opens the door to rampant propaganda and deceit, mainly for those who continue to regard victory over the monstrous as having top priority. If you're still reading this, your opponents are probably diehard triumphalists. Regardless of their metaethical views, triumphalists will always talk as if the reality of mind-independent morality is there for all to grapple with. If you retort with "No, it's actually not, but hear me out anyway because we can still construct our ethics, just how existentialists taught us that we can fabricate our own meaning!" the demagogues and their lackeys will make short work of you.

Hell, I will make short work of you.

Supererogation:

·

No.

Better is simply better. There is no non-arbitrary point at which the

betterness of an act goes from "morally recommended" to "morally

required". If I see something as axiologically better, I'll see it as morally better and even morally praiseworthy insofar as

the proper course of action is (1) reasonably foreseeable to the agent, (2) poses zero indirect effects on the afore-broached unpredictable future. If you want to make something

"obligatory" in a meaningful sense, simply criminalize its

violation/negation. If the violation/negation is unworthy of being

criminalized, despite it being morally obligatory, you are saddled with a hollow conception of "obligatory"

anyway. It's a law thing, not an ethics thing.

·

You

might now say "but you're a backer of lexical-threshold welfarism, you don't fret over

mild pains to start with, so there has to be some room for

recommended yet non-required acts" and to this I say: Given just how much

intolerable agony exists in the world right now –– easily preventable and well beyond the lexical tipping point –– I see no

purpose in bringing up other, milder negatives that happen to be easily

preventable as well. More, if the welfarism in use is non-lexical, or is just partly so, in that it merely recommends improvements for those who are safely below the unbearable negative intensity, but sternly requires improvements for those who have tragically surpassed the same negative intensity, I would distance myself from such a welfarism.

I don't believe we should recommend improvements to experience-clusters that altogether avoid the negative benchmark, otherwise we burden ourselves with having to account for silly cases wherein telling a harmless lie to your favorite person in the world is softly recommended (though not required!) when it prevents a scumbag from dealing with unwanted hiccups for longer than they'd care to. With any summative welfarism that gives priority to all sensorial preferences over all non-sensorial ones, this is precisely what would happen. A single sensorial aversion (to avoid hiccups) would reign over any number of non-sensorial aversions (to not be deceived).

Disclaimer: Shrewd readers have already figured out where all of this is heading: I am saying that a hypothetical world that guarantees all inhabitants complete freedom from enduring any and all agony near/at/above the lexical-threshold set-point is a world that has no need for prescriptive morality from the outset. In picturing such an unlikely world, I can see how the need for prudence would remain firmly in tact, and perhaps the need for etiquette too. Those leniencies aside, any additional work emanating from the robustness of the ought would be redundant and lose prescriptive import.

I don't believe we should recommend improvements to experience-clusters that altogether avoid the negative benchmark, otherwise we burden ourselves with having to account for silly cases wherein telling a harmless lie to your favorite person in the world is softly recommended (though not required!) when it prevents a scumbag from dealing with unwanted hiccups for longer than they'd care to. With any summative welfarism that gives priority to all sensorial preferences over all non-sensorial ones, this is precisely what would happen. A single sensorial aversion (to avoid hiccups) would reign over any number of non-sensorial aversions (to not be deceived).

Disclaimer: Shrewd readers have already figured out where all of this is heading: I am saying that a hypothetical world that guarantees all inhabitants complete freedom from enduring any and all agony near/at/above the lexical-threshold set-point is a world that has no need for prescriptive morality from the outset. In picturing such an unlikely world, I can see how the need for prudence would remain firmly in tact, and perhaps the need for etiquette too. Those leniencies aside, any additional work emanating from the robustness of the ought would be redundant and lose prescriptive import.

Ethics Of Belief:

· Epistemic Evidentialism > Prudential

Evidentialism > Moral Evidentialism

I think I'll stop here. I've got tons more clip-show content to finalize though, ranging from "descriptive takeaway" to updates on civic and governmental issues. Maybe I can wrap all of that up before the month is up as well.

In any case, it'll be a different post. This one ran long.

In any case, it'll be a different post. This one ran long.

Read my posts about how moderate pain doesn't count morally so that you can feel free to smack people and animals around BUT JUST LIGHTLY ENOUGH!

ReplyDeleteWow...still no reply explaining how what I said doesn't accurately represent you saying "a hypothetical world that guarantees all inhabitants complete freedom from enduring any and all agony near/at/above the lexical-threshold set-point is a world that has no need for prescriptive morality from the outset." I take your DEAFENING silence as an implicit admission that you have no moral objections with someone causing moderate suffering by smacking people around, which is bonkers. Either that, or you're too chickenshit to defend that quote against the accusation. So which is it?

ReplyDeleteNo, and yawn. I'm just too low on leisure time these days to jump at the opportunity to respond to lame ass argumentum-ad-absurdum shit from obvious trolls looking for a way to take the piss. Your example assumes that the people/animals smacked around wouldn't feel a negative add-on effect psychologically due to being harassed for no good reason by another person. A person who, presumably, doesn't go around breaking laws willy-nilly and is therefore a trusted member of the community, or an acquaintance, or even a friend. If an otherwise stable person singles you out for light or moderate smacky time, it's not just the smacks per se that cause the harassed party suffering. Recall that I repeatedly qualified lexicality with "near/at/above" in my post. This would be an example of one of those "near" edge-cases that should be taken seriously. The tiny bit of pain caused by the smack is not the whole story.

DeleteNothing stops hedonists (or welfarists broadly speaking) from drawing distinctions between enumerating and evaluating qualitative experiences.

If the proposed lexical theory simply enumerated the pains caused directly by the smack, then you actually might have a legitimate concern. But any sophisticated welfarist will know to include the indirect effects (i.e. psychological distress) as well, and to perhaps let those override the numerical bits.

Additionally, it's been shown that most people prefer 35 seconds of intense pain, followed by 5 seconds of milder pain, compared to just 30 seconds of intense pain without any fading effect at the end. Even under hedonic theories, a case can be made that what matters overridingly is the person's subjective conception of the pain and not the objective quality of it.

So if I'm understanding you correctly, it is better to rape a woman than to perform an act of tiny sexual misconduct against another woman if the raped woman's subjective conception of being raped is non-lexical while the other woman's subjective conception of being sexually harassed is "near" or "at" or "above" lexical. So in that case... you would rape Woman1 in order to avoid having to harass Woman2 and people calling you morally insane for it would be dismissed as "the folk."

ReplyDeleteLMFAO. What are your opinions of #MeTOo?

Why would the act-type of the perpetrator matter more than the toll taken on the victim? Aren't you just kowtowing to the happenstance of intuition? That is; the blind forces that instilled intuition in us in the arbitrary ways they did?

Delete"Why would our judgments, and our emotions, vary in this way? For most of our evolutionary history, human beings – and our primate ancestors – have lived in small groups, in which violence could be inflicted only in an up-close and personal way, by hitting, pushing, strangling, or using a stick or stone as a club. To deal with such situations, we developed immediate, emotionally based intuitive responses to the infliction of personal violence on others. The thought of pushing the stranger off the footbridge elicits these responses. On the other hand, it is only in the last couple of centuries – not long enough to have any evolutionary significance – that we have been able to harm anyone by throwing a switch that diverts a train. Hence the thought of doing it does not elicit the same emotional response as pushing someone off a bridge. Greene’s work helps us understand where our moral intuitions come from. But the fact that our moral intuitions are universal and part of our human nature does not mean that they are right. On the contrary, these findings should make us more skeptical about relying on our intuitions. There is, after all, no ethical significance in the fact that one method of harming others has existed for most of our evolutionary history, and the other is relatively new. Blowing up people with bombs is no better than clubbing them to death. And surely the death of one person is a lesser tragedy than the death of five, no matter how that death is brought about. So we should think for ourselves, not just listen to our intuitions."

From: https://www.utilitarian.net/singer/by/200703--.htm

"you would rape Woman1 in order to avoid having to harass Woman2"

I wouldn't, actually. But not because of the interests of Woman1 alone. Instead, my own interests would tip the panoramic harm scale, seeing as I have been psychologically conditioned to find rape-the-act-type to be as repulsive as just about anything a human can do. Dealing with the aftermath of raping someone would be far worse for me compared to dealing with the aftermath of pinching someone's ass (or whatever).

But that's just another contingent reason. It doesn't reflect badly on anything in the post, including the recommended lexical orderings of harms. If you remove my interests from the equation, or augment my psychology such that I no longer feel repulsion at the prospect of committing the more taboo act-type, then what could conceivably justify the choice to inflict far more harm on Woman2?

It's the equivalent of believing that it is morally better to punch a person who will get seriously hurt by the punch than it is to fire a shot at a human who is wearing a bulletproof vest, and who therefore won't feel a thing. All because shooting a bullet at someone can be viewed as "an attempt to murder" whereas punching them in the face (which is unprotected) is seen as far less taboo. Fuck off with that.

How many women have you raped since you wrote this?

ReplyDeleteLose the R between the o and the a. Stay true to yourself.

Delete